In August, the YouTube beauty vlogger Marlena Stell uploaded a nine-minute video titled “My truth regarding the beauty community” to her channel, which currently has 1.4 million subscribers. Though she refuses to name names (“I don’t want, by any means, for this to be part of any of the drama,” she says), the video is an attempt to shed light on the rapacious greed within the beauty influencer community.

“There are thousands of beauty influencers that want to make a name for themselves,” Stell says at one point. “They want to share their love of makeup. They want to do something they’re passionate about and support their livelihood by doing something they love. Some, unfortunately, are doing it because they want to be ‘famous.’ They want to have a nice paycheck. They want to go on trips. They want to have the fame and not share the love within the beauty industry.”

She goes on to share the frustration she experienced working with beauty influencers to promote her own makeup brand, Makeup Geek. “We haven’t been mentioned much, and part of the reason why is we haven’t been willing to pay influencers massive amounts of money. We don’t have the big funds to do that … We don’t have $60,000 to pay someone to make one video.” At one point, Stell hints that influencers have tried to extort her. “I’ve been told that if I don’t pay this amount for a video, they’re either going to talk bad about Makeup Geek, or they’re not going to talk about it at all.”

Though Stell’s refusal to “name names” makes it difficult to determine what sparked her video, its posting happened to coincide with a controversy that was, at that point, exploding throughout the beauty influencer industry. Manny Gutierrez, a beauty vlogger with close to 5 million YouTube subscribers, had been accused of being paid to start a feud with a startup eyelashes company, possibly with the idea that said feud would lead to more sales of the product. Both he and the lashes company denied that such collusion had taken place, but the fallout from the accusations was immense, with those involved claiming to be the recipients of death threats, blackmail, and all sorts of online invective.

This is far from the only controversy to erupt from the world of influencer marketing recently. Currently a multi-billion dollar industry, influencer marketing is a neologism used to describe whenever a popular online figure is paid to promote a product or service within their social media feed. Spend any time on Instagram or YouTube, and chances are you’ll encounter these stylish, photogenic influencers who hawk clothes, makeup, and nutritional supplements, often with a #sponsored hashtag placed somewhere prominently within the post’s description.

The industry has grown rapidly in recent years and is projected to generate as much as $10 billion by 2020. As more and more brands have waded into the market, demand for influencers has gone up. “In 2016 an endorsement from a top-level influencer would generally cost about $5,000 to $10,000,” Wired’s Paris Martineau reported. “Now, brands are expected to pay well over $100,000 for the same placement.”

With so much money flooding into a largely unregulated, still-developing market, all sorts of ethical lapses are bound to ensue, and indeed they have. Earlier this year, for instance, several famous YouTubers began sharing heart-wrenching confessionals of their struggles with depression and burnout. In one of the most gripping examples of this type of video, the YouTuber Elle Mills screams at the camera, “This is all I ever wanted. So why the fuck am I so fucking unhappy?” These videos were regarded as an inflection point for the YouTube community, with dozens of think pieces sprouting up about YouTube burnout and the burden of chasing online fame.

But the tide of community goodwill shifted after many noticed that several of these YouTubers ended their videos by promoting BetterHelp, an app that, for a price, connected you with a professional therapist with whom you could chat virtually about your mental health issues. Users reported shoddy service from the app and filed dozens of complaints with the Better Business Bureau. Soon, these famous YouTubers who had shared their raw, personal stories were accused of cynically exploiting the topic of mental health to line their own pockets. YouTube stars like Philip DeFranco paused their sponsorship collaborations with the app in response.

At least there was some measure of accountability in that instance. But as the influencer market grows, fraud is becoming more rampant, and it’s increasingly difficult to discern when influencers are engaging in above-board, ethical publishing, and when they’re taking questionable shortcuts that dupe both the brands that pay them and the social media followers they’re meant to influence.

Last year, The New York Times published an exhaustive investigation into the prevalence of social media bots, particularly those purchased by wannabe influencers and celebrities who want to inflate their importance online. Over a period of years, a company called Devumi “sold about 200 million Twitter followers to at least 39,000 customers,” including famous athletes, chefs, and reality TV stars. In some cases, these customers then turned to brands and touted their inflated following when selling sponsored posts. The Times article points to “two young siblings, Arabella and Jaadin Daho,” who “earn a combined $100,000 a year as influencers, working with brands such as Amazon, Disney, Louis Vuitton and Nintendo.” Both were shown to have employed the services of Devumi to purchase bot followers.

Brands have become increasingly aware that they’re the target of such fraud, and an entire cottage industry has sprouted up to help them keep the influencers they work with honest. A platform called Sylo, for instance, can hook up to an influencer’s social media account and analyze its followers for signs of bot activity, assigning it a score that determines its percentage of bot followers. It’s not uncommon for brands to require in their contracts that influencers be subjected to this type of analysis before an engagement begins.

Some of the major tech platforms have stepped in and attempted to regulate influencer marketing within their own ecosystems. Both Facebook and YouTube rolled out disclosure guidelines that allow you to denote a post as containing branded, paid-for content. Recently, Instagram announced it was cracking down on apps commonly used by influencers that generate automated likes, comments, and follows on other users’ accounts. Instagram warned users who continued to use these apps that they “may see their Instagram experience impacted.”

There’s also the consumer angle to consider. It’s becoming increasingly difficult for the average social media user to determine when a post showcasing a particular fashion item or other product is organic or sponsored. BuzzFeed reporter Katie Notopoulos runs a regular column in which she tries to discern whether celebrity social media posts are ads. “One thing that’s clear is that even those of us who are pretty savvy about this kind of stuff are often truly confused about celebrity Instagram posts,” she wrote.

To make matters even more confusing, wannabe influencers are now regularly uploading posts that are designed to look like they were paid for, even though they weren’t. That’s according to The Atlantic’s Taylor Lorenz, who reported recently that these aspiring Instagram stars are employing a fake-it-til-you-make it strategy, with the idea that the only way to attract sponsorship money is to pretend like you’re already swimming in it. “People pretend to have brand deals to seem cool,” one such practitioner told Lorenz. “It’s a thing, like, I got this for free while all you losers are paying.”

You may be asking yourself at this point what the government has done to step in and curb this abuse. For the past year we’ve watched as Congress has hauled in tech executive after tech executive to force them to answer for the malevolent practices carried out by their users. But while these executives were grilled on topics that included data collection, influence from foreign actors, and alleged bias against conservative voices, virtually none of the discussion touched on influencer marketing. What talk there was about automated bots was focused on the Russian variety, not those meant to inflate the influence of celebrity chefs and athletes.

That’s left most of the industry regulation to federal agencies, particularly the Federal Trade Commission. Stretching back to the late 2000s the FTC has been issuing guidance on how sponsored content should be disclosed online. Generally, the rule is that if there’s any sort of relationship, paid or otherwise, between a social media poster and brand that isn’t immediately obvious to the average user, then that relationship should be disclosed. Last year, the FTC participated in a Twitter chat in which the agency revealed that the disclosure tools that platforms like Facebook have put in place are not sufficient.

Legal actions have been scarce, and when the FTC has gone after a bad actor, it’s usually a brand that’s failed to issue firm disclosure guidelines to paid influencers. For instance, the FTC went after Warner Bros for hiring famous YouTubers to promote one of its games without disclosing that they had been paid. It also reached a settlement with Lord & Taylor for doing the same with fashion bloggers. In instances when it has targeted actual influencers, the FTC has mostly issued warning letters demanding they clean up their act.

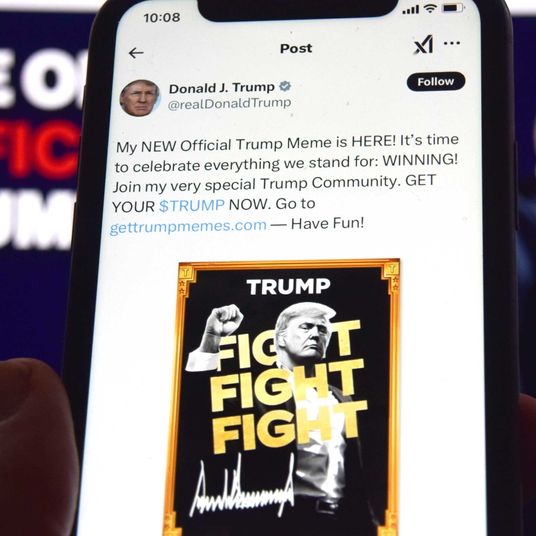

One of the most prominent legal actions against influencers came this year when the Securities and Exchange Commission announced a settlement with Floyd Mayweather Jr. and DJ Khaled for “failing to disclose payments they received for promoting investments in Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs).” The two paid a combined $700,000 in penalties, but the SEC was likely relying on their celebrity status (or, dare I say it, “influence”) to ensure that its guidelines against such shady behavior received widespread coverage.

But these punitive actions only represent a tiny portion of the ethical infractions, illegal and otherwise, that are carried out within the influencer marketing world every day. With the rise of “nano” and “micro” influencers – social media personalities who are able to sell promoted posts despite only having a few thousand followers – this world has become too fractious for any single government agency to monitor effectively.

Of course, many would have once said the same about Facebook and Twitter’s ability to ward off foreign interference in U.S. elections, but the increased media scrutiny and political pressure forced these platforms to invest millions of dollars and hire thousands of new employees to combat such activity and increase ad transparency. What may be awaiting the influencer marketing industry is a “Cambridge Analytica moment,” a form of fraud so calamitous that industry groups and tech platforms are shamed into adopting more drastic measures to police bad behavior.

In the near term, however, we have a divided Congress and an administration that isn’t exactly pro regulation. What we’ll likely see is increased scrutiny and coordination among industry players. The major tech platforms and ad agencies have already teamed up to develop a number of new tools to combat the $8.2 billion ad fraud problem, and these same companies are starting to take influencer fraud more seriously. Already we’re seeing major brands like Kellogg’s tighten up their policies for how they engage with influencers, changing the metrics by which campaigns are judged so they’re less likely to be gamed. Unilever, one of the world’s largest advertising buyers, announced last year that it would no longer work with any influencer that purchased followers. Of course, not every brand has the resources of a Fortune 100 company to manage its marketing, so the industry is still awaiting more scalable solutions.

For now, we’ll just have to settle for the creeping cynicism that nothing we see on Instagram is truly authentic. As one wannabe influencer told The Atlantic’s Taylor Lorenz to justify the fact she was misleading her social media followers, “They just assume everything is sponsored when it really isn’t.”