Remember rock stars? With Bob Dylan and ‘Dont Look Back,’ D.A. Pennebaker invented the ideal

While Bob Dylan was busy creating his legend in Greenwich Village folk clubs, D.A. Pennebaker was redefining realism in American filmmaking. In September 1961, folk impresario Albert Grossman tipped a New York Times journalist to Dylan’s set at Gerde’s Folk City. Dylan was still very new to New York, and had spent the past several months gigging around and inventing his back story to anyone who would listen. “Dylan was acting when he was simply walking down the street,” critic David Hepworth wrote about his early years. The glowing Times review, titled “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist,” ran a few days later, and Dylan carried the clipping around in his pocket.

A few months earlier, Life magazine writer/editor Robert Drew founded Drew Productions with Pennebaker and London-born filmmaker Ricky Leacock. The trio wanted to bring a Life photo-essay’s sense of candid immediacy to the moving-picture world, a task that required engineering innovations as much as new aesthetics. Pennebaker, an MIT graduate and former engineer, was up for the challenge. In about a year, they staged a revolution in realism by loading the new, lightweight Auricon and Éclair 16mm cameras with fast film stock that could pick up good images in available light, and synchronized the cameras with portable Nagra tape recorders using the pulses of quartz crystals, like a wristwatch.

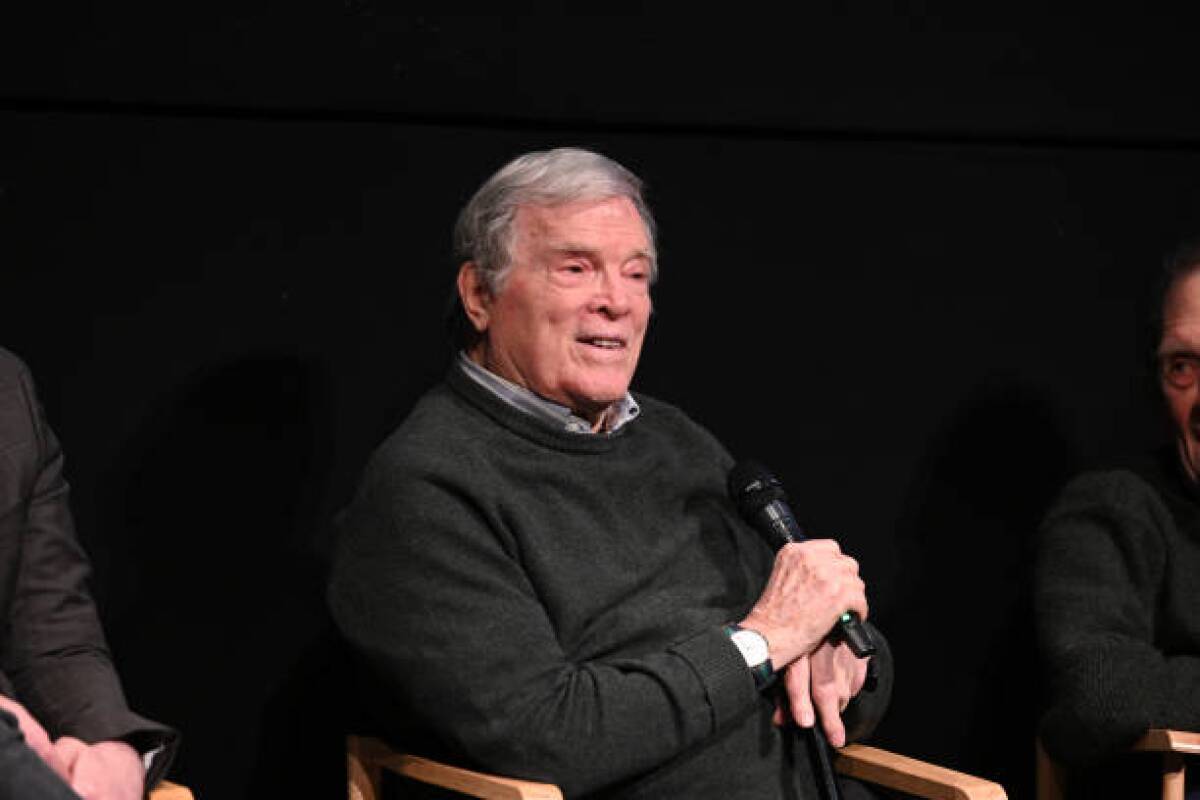

Drew dubbed the trio’s new approach “direct cinema,” and Pennebaker became fond of its core aesthetic and concept: long, uninterrupted takes, often shot in close-up, that could reveal something new and deep about the person being filmed. Unlike its artier French contemporary cinéma vérité, in which the filmmaker’s hand was always evident, direct-cinema filmmakers practiced a non-interventionist mode, in which the director was a fly on the wall. Pennebaker once compared it to peeking through a window.

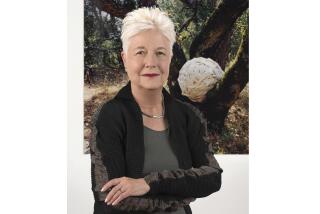

Never wavering from this simple idea for the next six decades, Donn Allen Pennebaker, who died Thursday of natural causes at age 94, spent his remarkable career documenting improvised moments amid the tightly choreographed worlds that grew around charismatic public figures. It is no coincidence that his best work was based around political rallies and rock concerts. 1960’s “Primary,” which he edited, and 1993’s “The War Room,” which he directed with his wife, Chris Hegedus, are the two best films devoted to the intense, behind-the-scenes drama of national political campaigns.

But it is Pennebaker’s work with rock musicians that cemented his status as one of America’s great filmmakers of any genre. “The very nature of film is musical,” he once said, and few if any visual artists had as much impact on the iconography of rock’s most fertile period. Pennebaker’s camera was there at the dawn of the American rock festival, documenting Janis Joplin wailing, Jimi Hendrix blazing and Otis Redding testifying at 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival. Six years and several rock ‘n’ roll lifetimes later, with that iconic Monterey Pop trio dead, Pennebaker documented rock’s most celebrated theatrical denouement: David Bowie’s final 1973 performance as his Ziggy Stardust alter-ego.

Before Monterey and Ziggy, however, came “Dont Look Back,” which captured the Big Bang of rock stardom that permitted Monterey and Ziggy to exist in the first place. Three years after that fateful 1961 concert, Bob Dylan was attempting to shake off the voice-of-a-generation status he’d earned before the age of 25. In 1965, Greil Marcus writes, Dylan “seemed less to occupy a turning point in cultural space and time than to be that turning point.”

Wisely, when Dylan’s then-secret girlfriend Sara Lownds, who worked at Time-Life, recommended Pennebaker to Grossman, the filmmaker was less interested in making a concert film than using direct cinema to capture this elusive character in the wild, in the process of a massive transition. The rare moments where Dylan is shown alone in the film are, ironically enough, his performances in front of thousands of fans. Pennebaker never shows the live crowds, though. During the concert scenes — which amount to only about 15% of the film — only a klieg light separates Dylan from the stark black backdrop of each venue.

“I saw Dylan as a Byronesque pop figure, a guy who was inventing a whole new kind of mood in popular music,” Pennebaker recalled. “And once he’s made it, he looks out at everybody and says, ‘... you!’” In 1965, there was no real rock press — the first issue of Rolling Stone would not hit newsstands for another two years — and the most engaging moments of “Dont Look Back” involve the tempestuous Dylan engaging with representatives from a journalistic world that increasingly seemed like it was covering another planet. Poor Horace Judson, who was covering arts for Time, received the worst end of Dylan’s anti-establishment bile. Time had “too much to lose by printing the truth,” Dylan told Judson, before getting personal. “I know more about what you do ... just by looking, than you’ll ever know about me, ever.” Pennebaker had not only captured Dylan’s venom in gory detail, but, like a nature photographer in the wild, he’d captured in miniature an early example of the ever-widening gap between the mainstream and counterculture that would swallow the country whole by the end of the decade.

Though Dylan and Grossman were very hands-off with Pennebaker — who shot 20 hours of film with a single camera, often roping Dylan’s friends into audio duties — Dylan recommended one idea during their first meeting. He wanted to shoot a short film for his new single “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” his first American Top 40 hit. Pennebaker grabbed a few dozen pieces of white cardboard from a local dry cleaner, onto which Dylan, Joan Baez, and doe-eyed folkie Donovan Leitch — whose popularity mystifies Dylan throughout the film — drew the key words from each line. Some words were misspelled. Others didn’t even appear in the song. As he displayed and then threw each card to the ground, his expression unchanged, Dylan simultaneously emphasized the power of pop slogans and the sheer disposability of language. A year earlier with “A Hard Day’s Night,” Richard Lester and the Beatles had merged pop-rock’s ebullience into a feature film. With the “Subterranean” clip, Pennebaker and Dylan had outdone them by inventing the promotional music video, some 15 years before MTV.

With the benefit of hindsight, Pennebaker captured several other moments that augured the second half of Dylan’s legendary 1965. While Dylan strums through Hank Williams’ “Lost Highway” in a hotel room, his friend Bob Neuwirth tells him to play the song’s “rolling stone” verse, which he obliges. In another short scene, he ogles electric guitars through a shop window. That July, Dylan played his inflammatory electric set at the Newport, R.I., Folk Festival, and released the scathing “Like a Rolling Stone,” a song that felt like Dylan’s frustrations from “Dont Look Back” balled into a fist. This was also the moment, according to David Hajdu’s book “Positively 4th Street,” when Dylan and Baez were also growing estranged. Baez resented Dylan’s shift to more abstract lyrics, and was hurt when he insisted on performing alone. Hajdu quotes Pennebaker sound recordist Robert Van Dyke describing a scene that didn’t make it into the film: “He would fume at her so badly, he would spit at her. I had to cover the microphones with my hands, so they wouldn’t get wet.”

Often overlooked in accounts of “Dont Look Back’s” significant influence over rock culture and documentary filmmaking more broadly (a 2014 Sight & Sound poll voted it the ninth-best documentary of any sort) is that while it was shot during Dylan’s most transformative period, it wasn’t released widely until summer 1967, when Dylan had holed up in Woodstock, N.Y., with the Band. Documentaries about rock stars did not have the same cachet in 1965 that they do today, and after screening the film on college campuses for a year, Pennebaker finally found a San Francisco venue willing to run the film: San Francisco’s Presidio, which, Pennebaker often recalled, was more known for adult films than art-house documentaries. Perhaps direct cinema’s sense of filmic intimacy had a predecessor after all.

On the surface, “Dont Look Back’s” intimacy seems contradictory: For all of Pennebaker’s closeness, the film, as many critics noted at the time, reveals precious little information about its core subject. But as with rock ‘n’ roll mythology itself, the film’s primary pleasures lie in the tantalizing tension between authenticity and artifice that Dylan was negotiating on the fly while keeping anyone seeking simple answers at arm’s length. Five and a half decades later, whenever a musician cringes as a reporter asks her to describe her lyrics, a bit of “Dont Look Back’s” DNA is embedded in the gesture. The greatness of Pennebaker’s film is Dylan’s revelation of non-revelation, the only rock ‘n’ roll lie worth believing.

Eric Harvey is a journalist and assistant professor at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. His forthcoming book, “Who Got the Camera: Rap and the Rise of Reality,” will be published by University of Texas Press.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.