In June last year, the staff of Sheffield’s John Lewis department store began the sad task known as “de-rigging”: clearing shelves and boxing up goods to be sent for sale elsewhere. The city-centre store had been shut since the start of the year, and in March 2021, the John Lewis Partnership had announced that it intended to close the store for good.

Some employees said they were too distraught to take part in all the packing-up. But others volunteered to participate, wanting to bid farewell to their colleagues and the building some of them had worked in for decades. There was a lot of reminiscing, as well as an undercurrent of anger: “tears and laughter in equal measure,” one former employee told me. Some people took away souvenirs, including the store directories that had sat next to escalators and staircases.

In the store’s restaurant, a signwriter had painted: “We no longer have our store but we will always have the memories.” The surrounding wall was soon full of photographs arranged in the shape of a heart, and expressions of gratitude and sadness: “I walked in these doors on my first day, turned round, had been here 23 years”; “For 19 years I’ve been here looking after you and you looked after me – that’s what families do”. T-shirts were handed out, reading: “John Lewis Sheffield: Sept 1963-June 2021”. By September, after three months of work, the store’s five floors were empty, and a story that had run for 58 years apparently reached its end.

When I visited two months later, the building was shuttered and silent. Every ground-floor window was covered by pastel-coloured posters advertising John Lewis’s “virtual events” and click-and-collect services. No one needed any persuasion to talk about the closure. “It’s as bad as a death in the family,” one passerby told me. Then she checked herself. “Well, that’s a bit over the top maybe. But it really upsets me. It’s just always been there.” Other people mentioned the excellent customer service, fondly loved rituals like Christmas shopping and the January sales, and the modest pleasures of visiting an old-fashioned retailer, where “you could see what stuff was, and find out what was what”.

The closure in Sheffield is part of a story playing out across the world: the extinction of the archetypal department store, and a wider crisis for town and city centres. British Home Stores closed all 167 of its UK branches in 2016; two years later, House of Fraser, founded in 1849, went into administration. After Covid triggered the temporary closure of most shops and a mass move to online shopping, one of the biggest casualties was Debenhams, the middle-market high-street staple, which announced that it would close its remaining 118 stores, including in Sheffield, in January 2021. John Lewis announced its first closures – eight in total, including department stores and a few smaller outlets – in July 2020, and another eight six months later, including Sheffield. In total, since 2016, according to a study published last summer, 83% of the UK’s big department stores have closed.

Because of their size, purpose-built department stores are hard to put to new uses. A few have been successfully reinvented – as arts centres, indoor trampoline parks and education settings. But the rapid spread of vacant stores raises a huge question: if urban centres are not going to be dominated by shopping, what do we want them to be?

In most cases, the fate of empty stores is decided by the commercial property market. But in Sheffield, thanks to a deal struck just before John Lewis closed, the building, which occupies one side of a prized central square, is now owned by the city council, and is at the heart of plans for the city’s next wave of regeneration. Sheffield’s two newspapers are alive with debate about what should be done with it. A loose community of activists, architects and locals passionate about their city have pitched in.

“In Sheffield, we’re not waiting for a remote landlord to come forward with their ideas. We can shape this,” one of the leading figures in the debate, political economist Tom Hunt, told a meeting of councillors and citizens recently. The point, he insisted, was “to be bold, and show the world what a new city centre can be”.

The old John Lewis building might be transformed, or demolished; it could be sold, or kept for public use. As the debate intensifies, Sheffield is becoming a test case for where our urban centres could be heading, and who gets to decide.

As you walk from Sheffield’s railway station into the city centre, the first thing that hits you are the hoardings, crammed with boosterish slogans evoking a vibrant future: “There’s a new momentum to our city”; “Remixing the heart of Sheffield”. Behind them lies a series of construction projects, split between the expansion of Hallam University and a regeneration drive called Heart of the City, which promises “spaces to entertain, relax, experience, play, work, gather, shop and drink” (the lowly placing of shopping is no accident). Faced with hard times, the city has seemingly decided that the best course of action is simply to press on with building work.

This is a very Sheffield thing to do. The city’s modern history is bound up with the ruptures it went through 40 or so years ago, when its steel and coal jobs disappeared. Thanks to its Labour city council and the Sheffield HQ of the National Union of Mineworkers, the city and its surrounding area were rebranded as The People’s Republic of South Yorkshire, where the red flag flew from the town hall on May Day, and equality and solidarity were deeply ingrained.

There was another aspect of Sheffield’s postwar experience: a futuristic sensibility embodied by many of its buildings, and the music that began to emerge from the city in the late 1970s, made by such groups as Cabaret Voltaire, Heaven 17 and the Human League. The 1980s was a time of strife and resistance, but it also saw the city associated with glamour and global success – not least in the winter of 1981-82, when the Human League’s timeless single Don’t You Want Me reached No 1 in Britain and the US.

The John Lewis building seemed to embody all these aspects of Sheffield and its culture. After its conversion into a mutualised company in the 1920s, John Lewis’s employees became “partners”, entitled to share its profits. Their workplace combined the monolithic vastness of the industrial age with the forward-looking aesthetics of its cutting-edge architecture. The Sheffield store looked like the acme of what the department store was meant to be: simultaneously aspirational and democratic; a place anyone could come into and share the dream of plenty and endless choice.

Such was a vision rooted in the 19th and 20th centuries – of huge, palatial stores, stocked with everything anyone would want. Department stores sat at the heart of people’s shared experience, and popular visions of the future. They were also a cultural commonplace. In The Floorwalker (1916), Charlie Chaplin was let loose among munificent displays of goods and that thrilling invention of the previous century, the escalator. The Marx Brothers’ The Big Store (1941) featured a musical number titled Sing While You Sell, and a chase sequence involving chandeliers and mail chutes. Between 1972 until 1985, the British sitcom Are You Being Served? presented the fictional Grace Brothers as a microcosm of a befuddled country, riddled with sexual repression and class distinctions, and hilariously short of business sense.

Before John Lewis bought it, the Sheffield store was called Cole Brothers, a family business launched in 1847 by two drapers who styled themselves as “Silk Mercers, Shawl, Mantle and Carpet Warehousemen, Bonnet Makers and Sewing Machine Agents”. Cole Brothers became a byword for Sheffield, partly because of its location, at the intersection of two city-centre thoroughfares, Fargate and Church Street. Coles Corner, as the site was known locally, was a place where friends and lovers would meet. Long since demolished but marked by a plaque, it is now the site of premises recently vacated by Pret a Manger. But if you want a sense of the memories that once swirled around this small patch of the city, there is a beautiful, self-consciously nostalgic song called Coles Corner, by the Sheffield singer-songwriter Richard Hawley. The music was full of swelling strings, and a sense of the glimmer of cities at night-time, the enticing pleasures they offer, and the loneliness of someone yearning for a way into it all:

Cold city lights glowing,

The traffic of life is flowing,

Out over the rivers and on into dark

I’m going downtown where there’s music,

I’m going where voices fill the air,

Maybe there’s someone waiting for me

With a smile and a flower in her hair

Cole Brothers was bought by the Selfridges Provincial Stores Group in 1927, which in turn was acquired by John Lewis in 1940. But despite these changes of ownership, Cole Brothers retained its name, and in 1963 the store relocated to its gleaming new premises.

The new store occupied one side of a city-centre square, Barker’s Pool, facing the City Hall – a venue that has hosted everyone from Bob Dylan to Winston Churchill – and Sheffield’s cenotaph. It was designed by architects Yorke Rosenberg Mardall, whose founders came from the UK, Slovakia and Finland respectively. The building’s white exterior tiles came from Belgium, and its entrances were lined with Spanish granite. Because it was conceived at a time when the automobile was the embodiment of aspiration, it included a multistorey car park with 400 spaces. Inside were 60 departments, spread over five floors. “Gay colour is the keynote throughout”, declared the John Lewis Gazette in September 1963. An eight-page feature included a picture of the huge crowd that had swarmed through the doors on opening day, and detailed descriptions of its interior. “In the restaurant,” it noted, “the carpet can be removed in sections for dancing.”

For the next 40 years, in homage to local tradition, the Cole Brothers name remained on the building. It wasn’t until 2002 that the store was rebranded as John Lewis. In the meantime, the story of the city centre and its businesses had entered a new and difficult phase.

In 1990, Sheffield’s commercial life was radically reshaped by the opening of a vast out-of-town shopping centre. Meadowhall, on the site of a former steelworks, is so big it has its own railway station. When it opened, Meadowhall offered 180 shops and 12,000 free parking spaces. Within five years, it was attracting many millions of visits per year.

Meadowhall inevitably had serious effects on Sheffield’s city centre. One recent architectural history of Sheffield said Meadowhall had “sucked the lifeblood” from the streets at the city’s heart. The city centre needed to lure people back. In March 1999, the idea that its future might be built on something other than shopping was tested by the opening of the National Centre for Popular Music. Comprising four huge steel “drums”, the £15m Lottery-funded building failed to translate Sheffield’s musical heritage into a visitor experience, and the public found it underwhelming. It closed in June 2000.

Ambitious plans for a city-centre retail development to rival Meadowhall were scuppered by the crash of 2008. Eventually, the council launched a new regeneration project for a chunk of the city centre including Barker’s Pool, with less emphasis on shopping and a new focus on housing, offices, eating and drinking, and more. But John Lewis remained central to its vision. There was talk of moving the store, but what mattered was keeping it in Sheffield, as a magnet for “footfall”, and a symbol of the city centre’s economic vitality.

When accounts of Boris and Carrie Johnson’s refurbishment of their Downing Street flat quoted a visitor scoffing at the previous incumbents’ “John Lewis nightmare”, it located the stores within the subtle gradations and snobberies of the English class system. John Lewis may be sneered at by the more moneyed, but it is still seen by many as solid and accessible, and reassuringly upmarket. These were the qualities the council wanted Sheffield to hang on to.

As Sheffield council was working on its regeneration plans through the 2010s, the man who found himself at the centre of negotiations was Nalin Seneviratne. Born in London and raised in Liverpool, he came to Sheffield 13 years ago, and when we first met in November last year, he was Sheffield city council’s head of city-centre development. Well versed in urban planning’s technocratic vernacular, Seneviratne is also full of passionate, optimistic ideas about cities and their future. “Everything flows into the city centre,” he told me. “All our main roads flow into the city, all the rivers flow into the city and out again, the main railway station is here. Our two universities are in the city centre. So we’ve got great things to build on.”

Seneviratne began dealing with John Lewis in 2013. At that time, the company was offered potential new premises nearby. “They said, ‘We don’t really like that location – it’s too far from Marks & Spencer.’ We spent ages discussing where they would like to be,” he recalled. “They didn’t like any of the plans we produced. We said: ‘Well, what do you like?’”

One council insider told me John Lewis proposed relocating within the city centre, in a plan that involved digging a tunnel for a new underground car park and demolishing Victorian buildings. “It was bonkers,” they said. “Completely undeliverable.” At one stage, I was told, John Lewis raised the prospect of moving to Meadowhall.

In 2017, John Lewis told the council the store was going to stay put. But three years later, the pandemic triggered a crisis for the company. “In 2020, they said: ‘Unless you can help us with refurbishment costs, we’re going,’” said Seneviratne.

Desperate to avoid such a major closure in the centre, the council bought John Lewis out of its lease for £3.4m and agreed a new rent based on turnover. The cost to the company of being in the building would increase, but in return, the council agreed to contribute “a considerable amount”, according to Seneviratne, to the cost of the store’s first refurbishment since 1980. Suddenly, all seemed well: John Lewis would stay.

The decision to buy the lease, Seneviratne told me, was based on an acknowledgment that nothing in the city centre was certain. “Understanding that retail was changing, you couldn’t just sit there thinking, ‘Oh, department stores are the future,’” he said. “It was important to get control of the building.” The money would be used to fix up the basics: electrics, lifts and escalators. “So if they [John Lewis] did disappear, the council had a building that was fit for purpose.”

Eight months later, in March 2021, John Lewis made another unexpected announcement. Lockdown had kept the Sheffield store shut since January. The company said that, notwithstanding the obligatory consultation with staff, it now planned to permanently close it. “I almost fell off my chair,” said Seneviratne. “The speed and the timing of the decision, not even a year since doing the new deal – that was a shock. John Lewis had said: ‘We’re going unless you help us.’ So we helped them, and they still decided to go.”

Sheffield’s city council leader is a former miner named Terry Fox. He had been deputy leader when the bad news came in from John Lewis. “It was them that broke up this relationship with the city,” he told me. “Not us.” He went on: “I was absolutely gutted. And furious. On the back of Debenhams closing, it was knee in the stomach time, you know what I mean?”

When I contacted John Lewis and presented the city council’s side of the story, a spokesperson declined to give a detailed response. The company said it “had continued discussions for a number of years with the council to explore ways to help us remain in the city” but “it would not be appropriate to discuss these conversations further”.

“After serving Sheffield for 80 years it was an incredibly difficult decision to leave,” said John Lewis in a prepared statement. “Although financially challenged before the pandemic, we agreed a new lease for the store in the belief that through investment in the shop we could play a key role in the city’s regeneration. However, the effects of the pandemic – including three national lockdowns and the acceleration of the switch to online shopping – meant the impact on the store’s viability was too great.”

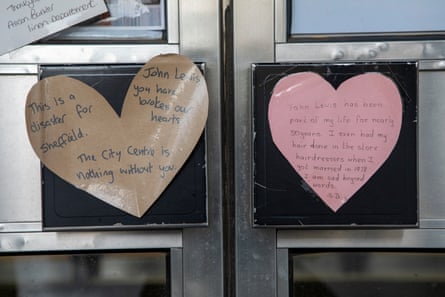

After news of the closure got out, an online petition demanding John Lewis reverse its decision quickly amassed 20,000 signatures. People posted messages and photos on the building’s windows. “I remember when my mum passed away, I came here to buy candles for her funeral,” one note read. “I was so upset and a lovely member of staff found a chair for me, sat me down and went off to find my candles. She was so helpful and patient, she couldn’t do enough for me. Yes, I can order online but I will never get that level of service so doubt I will shop with you again.”

Lana Barker worked at the store for 20 years, starting in the lingerie department, followed by seven years in children’s clothing. Last November, using some of her redundancy money, she opened a new lingerie shop called The Woman In Me, just outside the city centre. We had a long conversation, in between her serving customers. One was being treated for breast cancer. In the calm, sympathetic way Barker attended to her, you could see the years she had spent on the John Lewis shopfloor, and the kind of customer service people had so fondly talked about. “I loved working there,” Barker said.

After the closure announcement came the staff consultations, and the packing up. “Some people wanted to do it because of their attachment to the building, and I was one of them,” Barker told me. “I went through being frustrated, angry, upset, disappointed – the whole thing. And I was worried: what the hell was I going to do? I like to be organised. So for someone to suddenly say, ‘At the end of August, I can’t tell you what the rest of your life looks like’ – that’s panicking to someone like me. I’m only 43. It hit hard.”

Until January this year, Kate Josephs, the city council’s new chief executive, was set to be a key player in the next phase of this story. Raised in Doncaster, 23 miles away, she built a career as a high-ranking civil servant. For a time she worked in Barack Obama’s White House. From July to December 2020, she led the government’s Covid-19 taskforce, which drafted rules and restrictions, as well as overseeing other areas of policy on the pandemic.

Last month, she got caught up in the “partygate” scandal over allegations of a leaving party in the Cabinet Office. The gathering is being investigated by the Metropolitan police, and Josephs is also the subject of an investigation by the city council. The details remain unclear, but at the time of writing, she was on paid leave.

Around a month before all this broke, I met her in an upmarket cafe facing the old John Lewis building. She seemed full of enthusiasm for her new job, and the work she was involved in on the John Lewis building. “It was definitely a bold move by the council to appoint me,” she said. “I’m not a local government lifer, but I’ve been very supported. And I’m loving it.”

The announcement of the store’s closure, she explained, happened very soon after she arrived in Sheffield, whereupon it was her turn to make a bold move: asking people in the city to come up with radical ideas about what to do with the building. “I felt, I think in common with many people in Sheffield, a sense of personal disappointment,” she told me. “Growing up in the area, Cole Brothers was a place I used to go to. But I guess I pulled my socks up pretty quickly and thought, ‘Well, how are we going to think about this differently?’”

She said she was excited by the ideas that had come in. “We’ve had people suggesting climbing walls, or turning the inside into a kind of independent retail space, or knocking it down and creating a great public square.”

The council’s appeal to the public highlights the unique element of this story. After a department store closes, most local authorities have to wait for a private interest to buy and develop the space. Many stay empty for months, even years. In Sheffield, the future of the former Debenhams, just five minutes’ walk from Barker’s Pool, will be decided this way. But the council’s control of the John Lewis building opens up an array of possibilities.

The conversation about what should happen has been loud and passionate. Sheffield has two vibrant news outlets, the Star and the Telegraph, which have constantly covered the story. Of late, the latter has been energetically publicising one proposal in particular, for a football centre, building on the fact that the first rules of the game were drawn up in the city. Dreamed up by a consortium that includes a so-far unnamed “global sports brand” and fronted by a Sheffield-based company called Urbana Town Planning, the centre would host “have-a-go football experiences with celebrities, community pitches on the roof, and bars and restaurants on the ground floor opening on to Barker’s Pool”. Initial sketches also show what the people involved say will be a “residential tower”.

Two leading voices in the debate about the building’s future are both graduates of Sheffield University: Tom Hunt, deputy director of the university’s Political Economy Research Institute, and Adam Park, a local architect. In April 2021, they were given space in the Telegraph to call on the city council to convene “a big public conversation about how to reuse and reimagine the building”. To spark people’s ideas, they had come up with their own proposal: the John Lewis building reinvented as “Sheffield’s Covent Garden”. A design by Park showed cafes and bars on the ground floor, with “culture” and “retail” space above, and vertical extensions containing apartments.

When we met, they talked enthusiastically about Eindhoven in the Netherlands, where there are plans to turn an old shopping centre into a “green cultural quarter” with a new music venue and climbable “glass mountain”, and La Samaritaine, a revived department store in the middle of Paris, swathed in a new undulating glass shell, and now home to shops, offices, a nursery and 96 social housing units. “It’s still a department store downstairs, but they added three new storeys on top,” said Hunt. A similar extension could be possible here, he thinks. “Not a massive tower, maybe three storeys. You could do some really interesting stuff to create space for family housing, or for older people.”

What did they make of the football centre? “It looks like something out of the 1990s,” said Park. Hunt said: “The problem I’ve got is that it’s a big, single-purpose building – which, if it fails, is suddenly a major issue. You’re putting all your eggs in one basket, like the pop music museum, but on an even bigger scale.”

Both were wary of the kind of residential development – often poky student flats – that they said dominates the city centre. They also rejected the idea of pulling the building down and starting again. “We shouldn’t be demolishing buildings any more,” said Park. “Especially buildings that have a civic presence and a history like this one. But just from a sustainability point of view, the construction industry needs to think beyond demolition as a first option. There’s massive embodied energy in that building. Yes, it’s probably got asbestos in it. But you can take a building back to its concrete frame and build it back again, in quite a radical way.”

Just before Christmas, the John Lewis logos on the building’s exterior were dismantled. The entrance to the car park once again said “Cole Brothers”. At night, some lights stayed on. “There are people in there,” said Seneviratne, “but we don’t know what they’re doing.”

Along with Hunt and Park, the Sheffield Telegraph had organised a discussion about the building’s future at the City Hall. The muted, hesitant mood seemed to be partly down to the newly arrived Omicron variant, but also a sense of uncertainty about how any final decisions about the building would be made.

The most energised contributions came from a couple of the paper’s readers. One insisted she wanted another John Lewis, or something like it: a place “where you can go in look around and choose things – gifts, perfume, makeup”. Another was enthused by the idea of something “experiential”, perhaps a “social issues museum” centred on the struggles of women, people of colour and the LGBT community, or a sport museum. Others suggested a library, a creche and a reimagined shopping arcade. When Hunt spoke, he managed to frame his suggestions in big questions about democracy, participation and the future of the lived environment. “We can show the world what is possible,” he said.

The next day, the city council announced that John Lewis had agreed to pay £5m “to surrender their current lease and obligations”. The money would be put “towards the future redevelopment of the site”. Three consultancy firms had been employed to flesh out the council’s options. All highlighted the challenges in redeveloping the building, not least its extensive asbestos. One paper, by the urban planning agency Fourth Street, recommended knocking it down, opening up the surrounding space to the public, and putting up a new, smaller structure, with potential uses including a “library, archive and storytelling centre”, art gallery, music venue or sports facility, with an opportunity to “stack more private or commercial uses” on top.

The empty store is soon to be covered by a vast “wrap”, at a cost of £100,000, and a five-week public consultation by the city council about the future of the city centre is nearing its end. It sets out three broad options for the John Lewis building. Two involve demolition, then either the creation of a huge new public space, or Fourth Street’s mixed scheme. The third choice is to reuse the existing structure.

Later this year, the plans will become clear, but one person will not be involved: Nalin Seneviratne, who is about to step down as director of city centre development after 13 tumultuous years. “This is the longest I’ve ever worked for an organisation,” he told me. “Someone else needs to do the next chapter.”

As we walked around the city on my first visit, Seneviratne had talked about resisting private interests buying up public space, and the importance to cities of people’s memories. Street layouts ought to be left alone, he said, and the history of buildings has to be considered. The key to the future of the John Lewis building, he told me, lay in reflecting people’s longstanding relationship with what went on inside. “Staff and customers knew each other on first-name terms,” he said. “It was where people went for their first school uniform, their first pair of school shoes.”

“The trick will be to generate the same sort of love for whatever happens there next,” he told me. “Is it a space people can go and enjoy? Is it free to use? You could go into John Lewis and wander around, you needn’t have bought anything. People would meet in the restaurant, or go and have a coffee. All those things, to do with meeting people – how can that be recreated?”

What he said highlighted something that is often overlooked: the fact that what many dismiss as mere consumerism can be woven through with much deeper human needs and capacities, to do with interaction, self-expression and the way we mark the stages of our lives.

Like so many other places, as big stores lose their dominance, Sheffield is trying to find new outlets for those aspects of life. Around the corner from the old site of Cole Brothers, the council has bought a former Clinton Cards, and has begun turning it into a facility it calls Event Central, which will also enable outdoor gatherings on the street. Last year, it launched Summer in the Outdoor City, a series of events reckoned to have drawn more than 1.5 million people into the city centre. It may be some token of the thinking at work that, more than any other place I have recently visited, the centre of Sheffield has a striking number of places to simply sit down and do as you please.

The music, lights and voices Richard Hawley sang about may eventually be just as relevant to what happens here as old-fashioned commerce. “People will always want to come together,” Seneviratne insisted. “Mixing and meeting in places like this, being able to exchange ideas – that’s who we are as humans, isn’t it?”

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.