Christina Pappas figured she had reasonable odds of getting Taylor Swift tickets. She’d gotten an access code to the presale happening on Nov. 15. She blocked out two hours on her calendar to wait in the digital line.

And she had an advantage: Pappas, who is based on the West Coast, had purchased passes to Swift’s “Lover Fest,” a mini tour that was supposed to have taken place in 2020. It had been canceled due to the pandemic. Ahead of the “Eras Tour” presale, fans who had bought “Lover Fest” tickets received an email, with the subject line “Your Special Access to Tickets,” explaining that they’d “receive preferred access to participate.”

“My understanding of what was supposed to happen was that, first and foremost, ‘Lover Fest’ ticket holders were to be prioritized,” says Pappas.

Pappas registered for a “Verified Fan” code, which was needed to access to presale. (The other way to participate was to have a Capital One card.) She logged on to Ticketmaster at the start of the presale and was placed in a digital line. There were over 25,000 fans ahead of her. (She could tell by using a page-source trick Swifties were circulating.)

Finally, after waiting, Pappas made it to a seating chart of the stadium, where she could see available tickets. But she couldn’t click quickly enough to purchase any of them. “I was like, ‘Damn, that’s a bummer, and not what I expected.’ ”

Then, Pappas got a text from a friend. “I got in in 10 minutes, I got six tickets,” she says the message explained. The friend asked if she would like one. “I was like, ‘Definitely—thank you’ and also, ‘That doesn’t make sense.’ ”

The friend hadn’t had ‘Lover Fest’ tickets. Nor did she have another kind of supposed preferential access to the presale: Fans who had purchased a Midnights album or merch had received an email that Taylor Nation, Swift’s company, would “like to boost your place in line” for the tour.

Pappas thought it was weird that her non-boosted friend had snagged tickets so easily while she had been shut out. She knew she wasn’t alone: Other people who thought they had boosts but had not gotten tickets started sharing their frustrations on TikTok and other platforms. Because Pappas has a background in data analytics, she began trying to quantify what she was seeing. “I wanted to put numbers to the individual experiences and anecdotes everybody was sharing,” she says. She created a survey to learn more about other fans’ experiences and posted it on Reddit and Facebook.

It’s no mystery why these tickets were so hot: Swift, one of the biggest pop stars in the world, is going out on tour for the first time in four years at a moment when demand for gathering in person to scream-sing is especially high. But the fiasco around the tickets underscored two different issues: the challenge of getting tickets into the hands of die-hard fans, not scalpers looking to turn a profit, and whether Ticketmaster was really doing everything it could to handle the overwhelming demand.

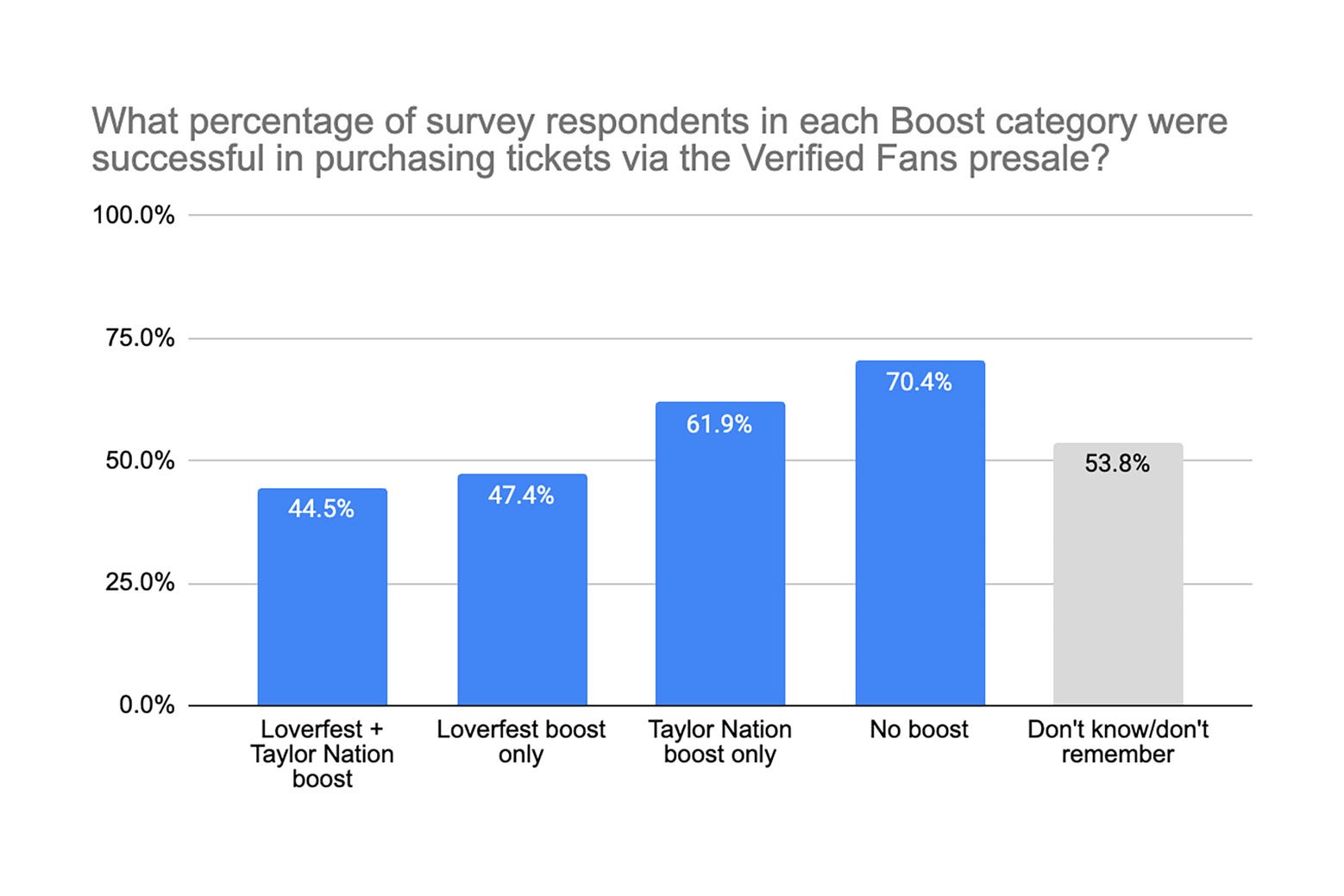

“I was blown away by the speed of the responses,” says Pappas of the more than 2,200 people who filled out her survey. When she examined the numbers, she became a little concerned by what she saw:

“My biggest takeaway from my data so far,” Pappas wrote to us when she shared her findings: “It appears boosts not only didn’t help, they actively harmed.”

You may laugh, but a botched ticket sale is pretty high-stakes stuff in 2022. On Dec. 2, lawyers sued Ticketmaster on behalf of over two dozen fans who were under the impression that the presale was supposed to be exclusive to “Lover Fest” ticket holders and those who had purchased Taylor Nation merchandise. “Only those individuals who satisfied either of these conditions would be allowed into the presale via a code as a ‘verified’ fan,” says the complaint. “Plaintiffs relied upon and accepted such terms and conditions, thereby purchasing merchandise and/or accepting the benefit from the canceled ‘Lover’s Fest.’ ” (It’s worth noting that this differs from the language in the boost emails, which promise preferred, not exclusive, access.) Perhaps even more gravely for Ticketmaster, in the wake of the messy presale the Department of Justice opened an antitrust investigation into parent company Live Nation, possibly as a precursor to reassessing the merger between the two companies, which it controversially approved in 2010.

Like Pappas, we’re taking it seriously too, which is why we sought second and third opinions on her data and analysis, an informal peer review.

Sarah Zelasky, a Harvard-trained environmental scientist (and co-author Shannon Palus’ cousin) calculated something called a z-score for the difference in the success rate of boosted vs. non-boosted ticket buyers. “You get a z of -6.427, which corresponds to a p-value of <0.00001,” she wrote in an Instagram DM. (It’s worth noting that Zelasky completed her calculation before Pappas closed the survey; responses were still trickling in.) That means “it’s very unlikely” that people with a boost had the same likelihood of buying tickets as those without a boost, she explained.

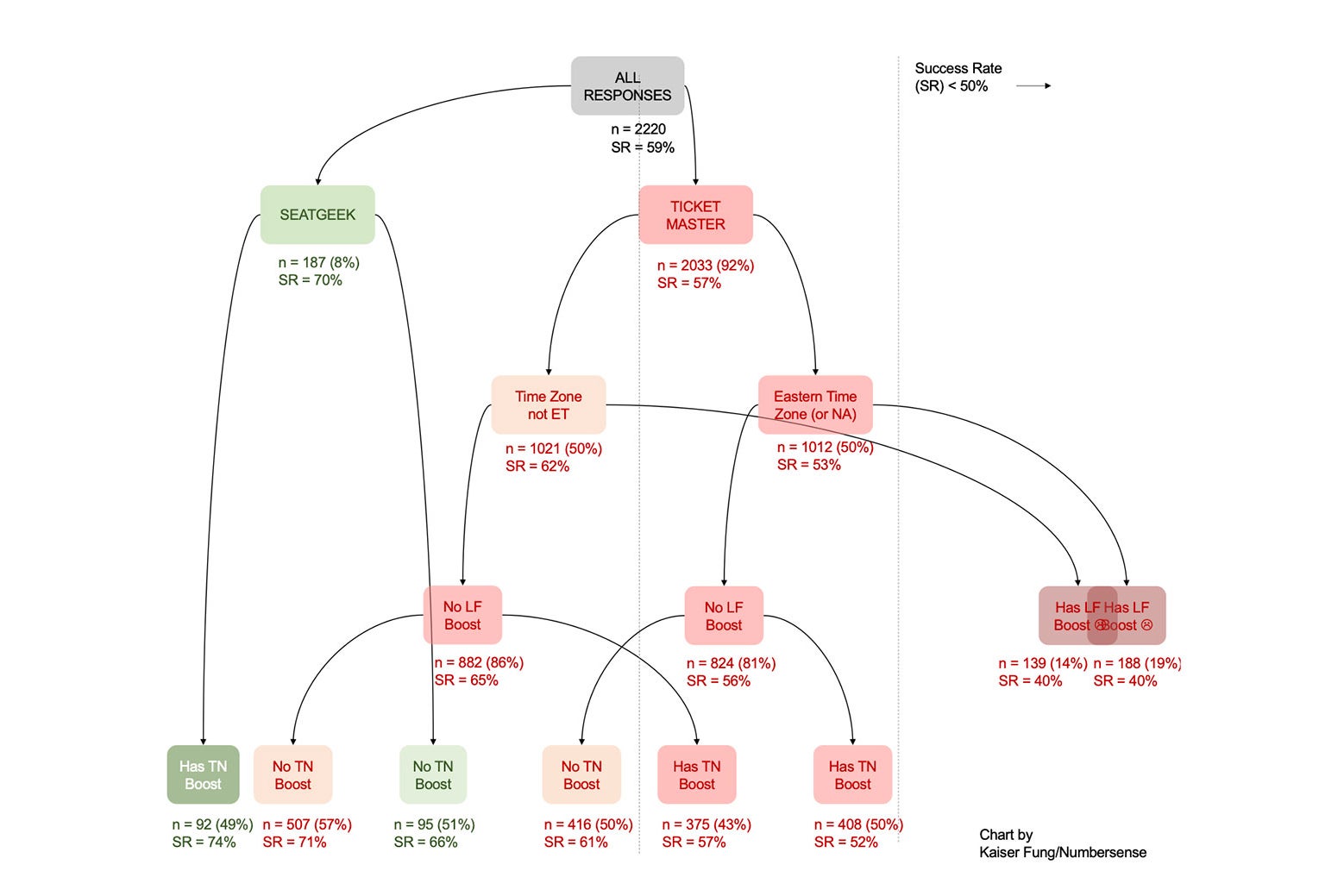

Andréa Becker, a medical sociologist at the University of California, San Francisco, offered an important observation on Pappas’ initial work: The survey had asked participants if they’d purchased tickets via Ticketmaster or SeatGeek, another ticketing platform used by a smaller number of stadiums, primarily in the Mountain time zone. By Becker’s calculations, those who had used Ticketmaster to try to purchase tickets had a 57 percent success rate, while SeatGeek users saw a 70 percent success rate. ”That’s a huge difference!” she wrote in an email. You can access Pappas’ data, as well as her analysis of the outcomes, here.

Taking Pappas’ raw responses, we ran our own analysis (completed by Kaiser Fung, the other co-author of this piece). The more than 2,200 responses give us a fairly solid sample size. (Though it’s worth noting that since the data was collected via an anonymous form online, we cannot validate these responses. Take this as preliminary research!) We carved the responses into multiple groups of fans who’d had similar experiences: by platform, then by time zone, then by whether they’d had a “Lover Fest” boost, a Taylor Nation boost, or both. You can see the results in this chart. Read it from the top down as a kind of choose-your-own-adventure that ends with the probability of getting tickets. Note that the all at the top refers to a group that had Verified Fan codes and was allowed to enter the presale.

These results confirmed that Pappas landed in the worst possible segment: Ticketmaster customers on the West Coast who’d received the “Lover Fest” boost had the lowest odds of actually obtaining tickets.

While the average Ticketmaster user had a 57 percent chance (or success rate) of scoring a presale “Eras” ticket, our analysis found that those who reported having a “Lover Fest” boost fared worse, not better: Instead of getting preferential treatment, these fans found the success rate dipping to 40 percent. The “curse” of “Lover Fest” inflicted worse pain for those in line for tickets at venues outside Eastern Standard Time: The boost cost them 25 percentage points of success rate, as compared with their time zone peers without the “Lover Fest” boost. Those with the boost who purchased tickets for EST venues lost 16 percentage points of success rate.

Some fans fared much better than Pappas. Specifically, 7 out of 10 fans who used SeatGeek made it through the line. Among this group, the Taylor Nation boost did improve one’s odds, albeit not meaningfully, to 74 percent. (For Ticketmaster users, the Taylor Nation boost appeared to backfire except when its impact was overwhelmed by the “Lover Fest” curse.)

Ultimately, our analysis found that boosting worked as expected for one group only: SeatGeek users.

This raises a number of questions: Do the results have something to do with Ticketmaster’s much larger scale of operations? Is it because of unbalanced distribution of tickets among time zones? Because SeatGeek had a more efficient system in some way? Or is it that SeatGeek had less-demanding fans who would have taken any seat and date? Maybe if you’d had a “Lover Fest” ticket and were based on a coast, you were just pickier about tickets, and by the time you made it through the queue and into the seating arena view on Ticketmaster, you decided that no, you weren’t willing to click as quickly as you could to get absolutely any seats whatsoever into your cart. The “Lover Fest” tour hadn’t been scheduled to go to the Midwest, so it’s possible that fans who bought tickets to faraway shows in the first place were more willing to jump at whatever tickets they were offered, cost or logistics be damned.

However, there are many examples of fans who scrambled as quickly as they could to grab tickets and were still unsuccessful. Sam Adams, a senior editor at Slate, received a Verified Fan code (though he did not receive an email indicating he had a boost). But he’s not sure a higher-priority spot in line would have even helped: Like Pappas, once he’d made it through the queue, he was unable to click on available tickets before they disappeared. He ended up getting floor seats through a separate Capital One sale the next day, with a card he’d applied for just for the occasion. He didn’t want floor seats, necessarily; those were just the ones he could successfully add to his cart.

Part of the reason “Lover Fest” boosts may have appeared not to work could stem from a misunderstanding about who was actually boosted. Lisa Hildenbrand, a Swiftie who lives in Indiana and goes by @LisaLuvsTaylor on TikTok, had gotten tickets to a “Lover Fest” show on the West Coast. She assumed that meant she would have the opportunity to get “Eras” tickets. But she hadn’t bought the “Lover Fest” tickets from her own Ticketmaster account—a friend had made the purchase, and then transferred them to her. She never got an email confirming that she’d received the “Lover Fest” boost, but she still felt confused when Ticketmaster did not send her a Verified Fan code. (She did get a merch boost—she has a lot of Swift merch.) It’s possible that some cases like Hildenbrand’s are showing up in Pappas’ data: people who reasonably figured they were going to have access because of their “Lover Fest” tickets but who hadn’t actually fulfilled Ticketmaster’s specific requirements to get that boost.

A nefarious read on this is that Ticketmaster deprioritized boosted fans. (Ticketmaster did not respond to a request for comment. A few days after the presale, Taylor Swift released a general statement about the broader fiasco on Instagram, noting that she hated trusting third parties to handle interactions with fans, as she had here, and was “trying to figure out how this situation can be improved moving forward.”) It’s impossible to tell right now what really happened, but what’s clear is that the chance of securing a presale ticket depended on a combination of factors: the ticket platform, the time zone, one’s boost (or lack thereof), and the type of boost. One other thing that’s clear: Even if you never make it to the Taylor Swift concert, you can entertain yourself endlessly with the presale data.