/media/video/upload/V.SABA_TVLiterature_01.mp4)

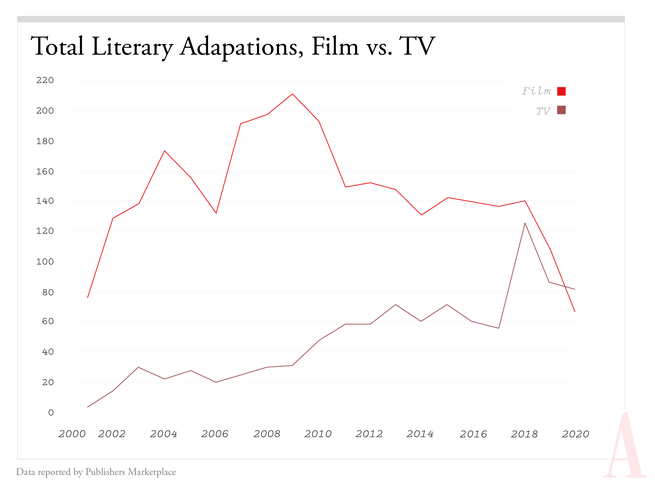

If you want a preview of next year’s Emmy Awards, just take a walk past your local bookstore. According to data drawn from Publishers Marketplace, the industry’s clearinghouse for news and self-reported book deals, literary adaptations to television have been on a steady climb. The site has listed nearly 4,000 film and television deals since it launched in 2000, and both the number and proportion of TV deals have increased dramatically in that same period. Last year, reported TV adaptations exceeded film adaptations for the first time ever.

Literary adaptations are big business. For streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu, they provide a reliable source of content for limited or multiseason series; Publisher’s Weekly reported in 2019 that Netflix was on a “book-buying spree,” and the company has shown no sign of slowing. Rotten Tomatoes cites 125 literary adaptations in development right now.

All of this has had a profound effect on the literary world. As you might expect, becoming a TV show increases a novel’s popularity enormously. Adaptations can drive book sales, as in the case of this winter’s breakout hit Bridgerton. The Regency-era bodice-ripper is not alone: A number of backlist titles, such as The Queen’s Gambit, have enjoyed a late-in-life revival thanks to Netflix’s attention.

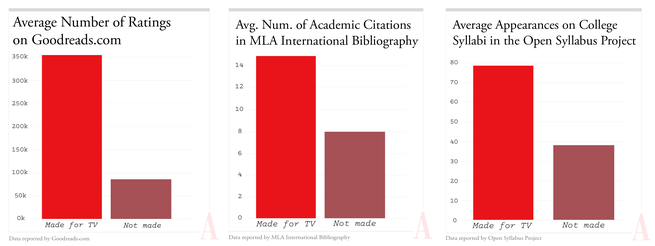

We see evidence of the adaptation effect in other measures of literary success as well. We compiled a list of about 400 21st-century novels that met certain criteria—inclusion in top-10 best-seller lists, critics’ picks, publishers’ comp titles, and so on. Within this group, a novel that becomes a show will receive about four times as many ratings on Goodreads.com as a novel that has never been adapted to TV or film. (Film still has a bigger effect, boosting a novel’s Goodreads ratings more than 1000 percent; TV nonetheless dramatically improves the fortunes of a novel.)

More surprising is that TV adaptations also correspond with a rise in a novel’s prestige. Adapted novels in our set have almost twice the citations of unadapted works in academic articles, and appear on about twice as many college syllabi. TV doesn’t just borrow highbrow status from the novel; it apparently sends some back. Of course, the world of unadapted literature is enormous—technically speaking, it comprises almost everything ever written. But our data set contains only books that have achieved some kind of prominence, so an effect of this size is striking. Nowadays, the first draft of the literary canon is being written in TV Guide.

Television adaptations are influencing every stage of a book’s life, including how it’s acquired in the first place. Scouts from networks and streaming services are talking more and more with publishers about big- and small-screen options at earlier stages of negotiations, in many cases before the ink on a book deal is even dry. Production companies such as Anonymous Content are bringing publishing-industry veterans on staff, and agencies and scouting firms are hiring specialists in literary development. Clare Richardson, a senior scout for film and TV at Maria B. Campbell Associates, one of the firms that works with Netflix, told us, “An important part of my job is having long-standing connections with literary agents and editors—what they’re reading, what they’re liking, what’s working. I’m trying to dive deep and find things as early as possible.” Richardson adds that simultaneous submission—that is, when a book deal and a screen option are negotiated at the same time—is common. Writers, agents, and editors have more incentive than ever to craft novels with TV in mind. The system rewards the adaptable.

So we wondered what kinds of novels were most likely to end up on screen. What qualities—of genre, structure, or style—make a novel seem most adaptable? We coded our sample of contemporary fiction not only for what has been successfully brought to TV, but also for what producers and scouts have optioned in the belief that it could be.

Reviewing that larger sample, we noticed several common features that unite texts as seemingly disparate as A Visit from the Goon Squad (which Jennifer Egan herself said she modeled on The Sopranos), N. K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer (all of which have been optioned for television). Although not every novel under contract for potential adaptation shares all of these features, they do seem to possess a consistent set of what we call “option aesthetics”: episodic plots, ensemble casts, and intricate world-building. These are the characteristics of contemporary fiction that invite a move from the printed page to the viewing queue.

Conventional wisdom among literary critics holds that a plot derives its meaning from its ending. Philip Marlowe solves the mystery, Elizabeth marries Darcy, and these concluding events are the reason the investigations and flirtations of the preceding text feel purposeful. They even determine the characters and setting: In The Da Vinci Code, Robert Langdon goes to Paris and meets with various colorful characters because foiling Opus Dei’s plot—and ending Dan Brown’s—demands it. As the literary scholar Peter Brooks puts it, “The end writes the beginning and shapes the middle.”

Yet this theory falls apart when it comes to television. The classic shape of a TV show is a potentially endless overarching plot (or none at all) structured by episodes. Each episode, of course, might have a highly coherent story with a well-defined ending. Think of Law & Order. A seasoned viewer can start a random episode at any point and know exactly how far away the ending is. The series as a whole, though, might get canceled tomorrow or run for a generation, which means it cannot be structured by its ending. Like day-to-day life, TV is all middle. For people who think about narratives as beginnings, middles, and ends, this is confusing and potentially frustrating (Aristotle: “Of all plots and actions the episodic are the worst”). If the action governs the characters and setting, and the ending governs the action, what happens when there is no ending?

The literature-to-TV pipeline turns this hierarchy on its head. The goal of being renewed for another season (or being the kind of book that could make it to multiple seasons) requires the ending to recede. Alden Dalia, a motion-picture executive at WME, explains that the difference between a potential film and a miniseries or full-blown show is not the arc or length of its plot, but rather characters “you become completely entranced with” and “a world you want to spend eight hours in, or 50 minutes each week.” In other words, the characters and the setting literally run the show.

As television scholars have noted, the plots and premises of “complex TV” are structured primarily around characters and their development: Viewers want to identify with, relate to, and follow characters. Given that, the adaptation economy may well be one of the driving forces behind the proliferation of what literary critics call “multiprotagonist fiction,” books with not a single protagonist (an Emma Woodhouse or Hercule Poirot, say) but a collection of main characters whose stories intertwine in surprising ways over the course of a single narrative. These become shows led by ensemble casts, a collection of actors who can carry multiple episodes and (perhaps) seasons. Most famous, of course, is George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones. But the trend sprawls beyond Westeros and includes literary adaptations such as The Leftovers, My Brilliant Friend, Little Fires Everywhere, The Underground Railroad, Watchmen, and Station Eleven.

Novels with ensemble casts adapt easily to the episodic structure of television; a chapter from the point of view of Arya Stark in the books becomes an episode about Arya, and an opportunity to explore that character’s unique identity. And if the goal of character-driven TV is audience identification, then multiprotagonist novels—particularly those that feature a diverse cast of characters—provide the greatest potential for maximizing viewership and boosting ratings.

The option aesthetics of contemporary fiction also affect the worlds those characters inhabit. Of course, world-building has long been a hallmark of science fiction and fantasy, evident in adaptations such as The City & the City and American Gods. But historical novels have also been particularly suited for adaptation, whether they are set in the 16th century (Wolf Hall), the 19th century (Alias Grace), or the 20th (Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald)—or in some alternate version of them (The Plot Against America). And recently optioned novels such as Oryx and Crake and The Power make clear that the near future is as compelling a setting as the recent or distant past.

Despite their different eras, these novels are similarly invested in a kind of world-building that draws the reader out of the present. Part of their adaptability is that exploring the rules of these brave new worlds—where handmaids buy groceries and enslaved fugitives catch trains—lends itself to inhabiting the perpetual middle that characterizes TV’s narrative form.

In the days before The Underground Railroad’s premiere, Amazon promoted the series with the tagline “Dare to not only change history, but to make it.” But making history can be expensive, as constructing “antebellum versions of five states … more than 3,000 costumes … a 15-structure plantation and … an actual train” can reportedly cost more than $1.5 million in a single day. And yet, far from being a deterrent to adaptation, this type of elaborate (and expensive) world-building is one of the elements of contemporary fiction that appears most attractive. Common to many optioned novels is what we might call high-production-value description—that is, writing that emphasizes its own enveloping intricacy. Describing the scene in which his protagonist, Cora, first encounters the underground railroad, Colson Whitehead writes:

It must have been twenty feet tall, walls lined with dark and light colored stones in an alternating pattern. The sheer industry that had made such a project possible … The steel ran south and north presumably, springing from some inconceivable source and shooting toward a miraculous terminus. Someone had been thoughtful enough to arrange a small bench on the platform. Cora felt dizzy and sat down … “It must have taken years.”

Just as Cora does, readers are meant to both notice and marvel at the descriptive details of the station, the “sheer industry” that transforms the “colored stones” into something “inconceivable” and “miraculous.” Likewise, in Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, the narrator describes the elaborate process by which Lila (like the costume designers for the novel’s HBO adaptation) crafts a cherished pair of leather shoes. Here, too, the artisanal labors of fictional description and production design are equated, as are the various forms of capital they produce: “Even though she was now obsessed with shoes,” Ferrante writes, “she still wanted to write a novel with me and make a lot of money.” Just as the alternate worlds of these novels structure the narratives that exist within them—after all, part of the reader’s pleasure is in figuring out just how things work in Margaret Atwood’s Gilead, China Miéville’s twin cities, and Whitehead’s united “states of possibility”—their self-consciously ornate style of description provides the basis for their potential success on the small screen.

Episodic plots, ensemble casts, and high-production-value settings—these are the features that, although not at all new to the novel (as flipping through George Eliot’s Middlemarch will quickly remind you), are newly central to fiction’s anticipatory relationship to the realities of streaming TV. But what does all this mean for readers? Is contemporary literature being dumbed down by authors, agents, and publishers motivated purely by profit and struck with a severe bout of adaptation envy? The short answer is no. From Charles Dickens’s stage-play adaptations to William Faulkner’s side hustles in Hollywood, novelists have always existed in a multimedia ecosystem that both subsidizes and shapes their work on the page.

As the figures and examples above illustrate, the rise of streaming and its love of literature have not only influenced which books are read, taught, and studied by scholars; they have also started to mediate the form fiction takes even if it’s never adapted at all. Whether or not authors themselves are keeping one eye on the television, the literary gatekeepers who decide which works reach bookstore shelves are. In all, a kind of currency exchange exists between literary fiction and prestige TV: Novels lend their cultural capital to the likes of Netflix and HBO Max in exchange for financial capital in the form of readers. While it might be tempting to think of this as the tail wagging the dog, it also places the novel, long reported dead, at the center of contemporary culture, where “must see” and “must read” TV are often one and the same.