A few weeks ago I was contacted by a journalist at the New York Times, who asked if I felt that film critics were losing touch with the tastes of the broader public. Naturally, I turned to the data to have a look at what’s going on.

I built up a database of 10,449 movies released in US cinemas between 2000 and 2019 (more details in the Notes section at the end). I then gathered data on their Metascores (to measure average critical score, out of 100) and IMDb users scores (to measure of audience views, out of 10).

I think it will be useful to breakdown what I found into three smaller questions, and then address each in turn. They are:

- Do critics and audiences have the same taste in movies?

- How are the two sets of scores correlated?

- If there’s a shift over time, what could be causing it?

Do critics and audiences have the same taste in movies?

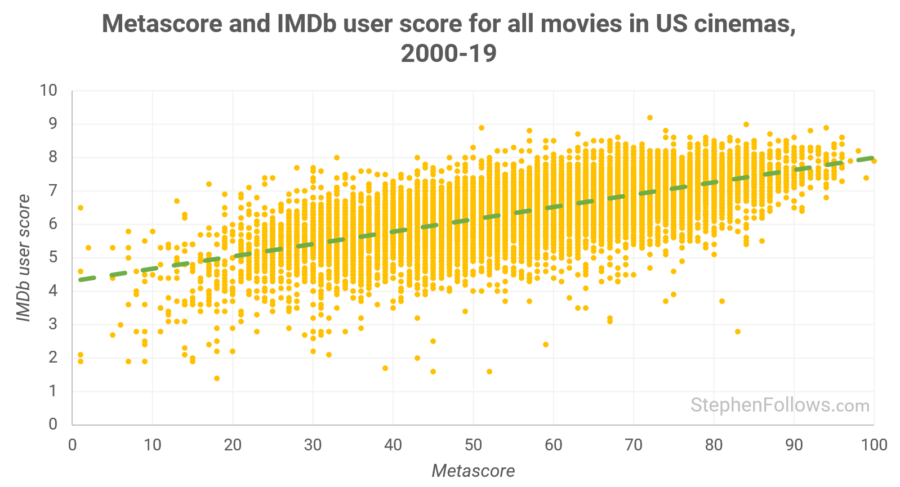

We need to start by looking at whether there is any link between the tastes of the two groups. Each yellow dot on the chart below is a movie in the dataset, displaying it’s Metascore and IMDb user score. I’ve also added a green trendline to help show the overall pattern.

We can see that there is a very rough trend in which audiences and critics do broadly agree. That said, many films show deviation from the trendline, and it gets particularly noisy at the “bad” end (to the bottom left).

As a side note, it’s interesting to see the agreement in the “good” quadrant (top right). It seems that the two groups agree most when they are talking about extremely good movies.

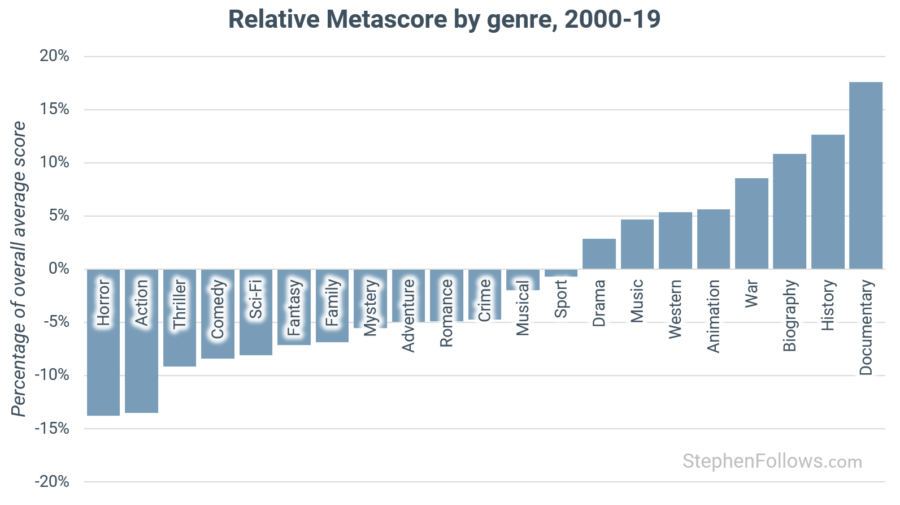

Next, let’s look at how each of the groups typically rates different genres. The chart below shows how critics rate each genre, expressed as a percentage of the overall average score. I.e. The average Metascore over this period was 58, so if a genre had an average of 63.8 then it would be shown as being 10% above average.

Documentaries, historical and biographical films are rated highest, with horror, action and thrillers the lowest.

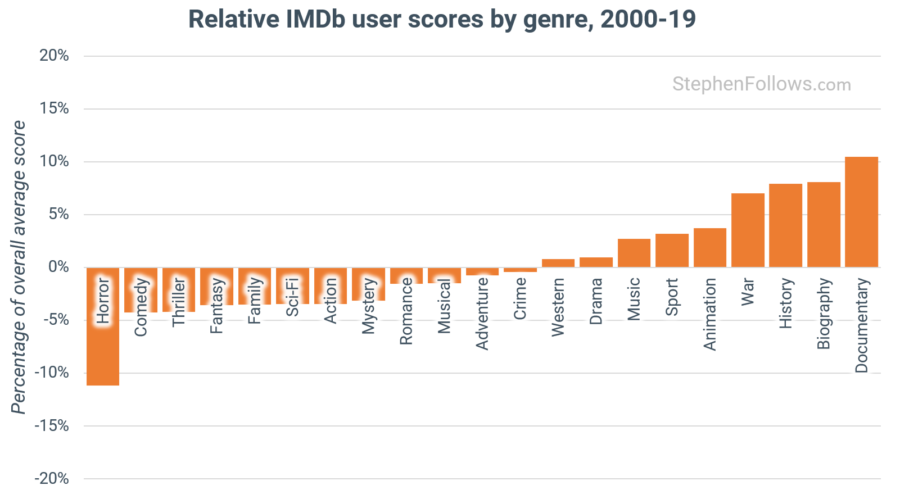

Using the same set of movies, we can use the same technique to look at how audiences on IMDb rate movies. We see very similar results; both groups had documentaries, historical and biographical films at the top and horror and thrillers at the bottom.

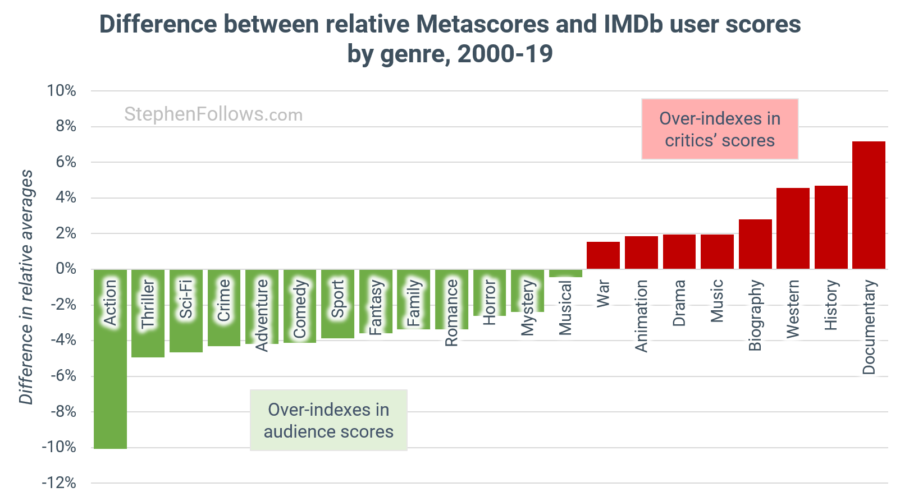

Overall, they are remarkably similar, albeit with a few differences. You may have spotted some of the areas of disagreement already but to make it even clearer, the chart below shows the same data but focuses on the difference between the two groups. You could see this as a measure of the difference between how much each group likes a genre. For example, while both groups rated documentaries the highest, critics did far more so than audiences.

This chart reveals that action, thriller and sci-fi movies could be called “crowd-pleasers” as they are preferred more by audiences than by critics. Conversely, westerns, historical films and documentaries are “critical darlings”, with a skew towards pleasing critics.

How are the two sets of scores correlated?

Ok, so now we have an understanding of the tastes of the two groups, let’s turn to measuring the extent to which their scores are correlated.

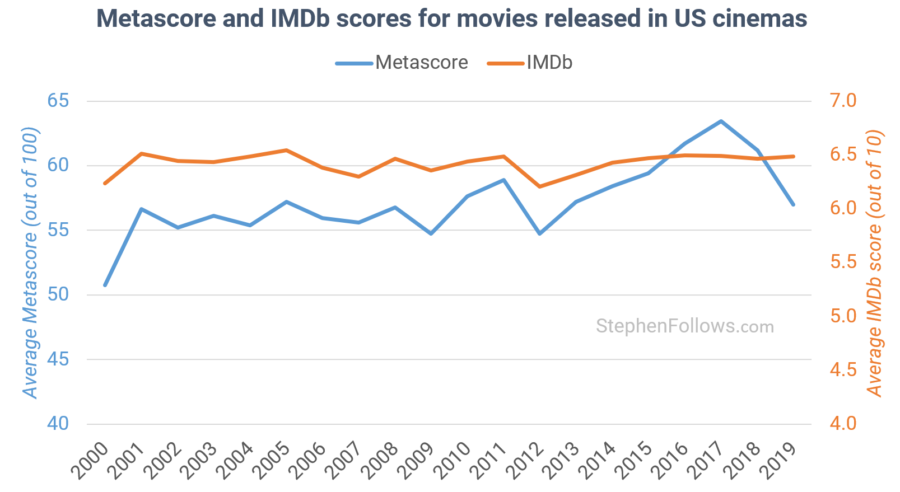

The chart below has two vertical axes, in order to allow us to plot both sets of scores. Which line is higher or lower than the other is irrelevant (as it’s a consequence of the axis thresholds) but what is of interest is the extent to which they rise and fall together.

It reveals that while IMDb scores have been fairly static of the two decades, critical scores started to rise around 2012, falling again in 2017.

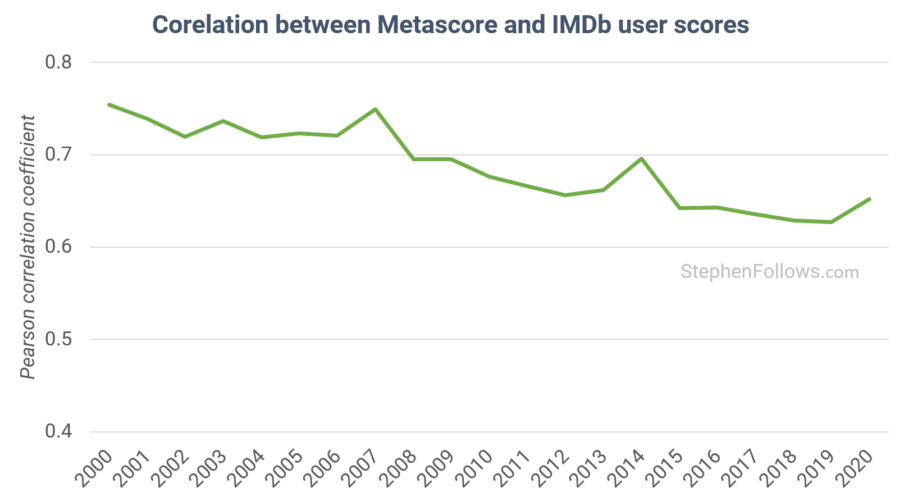

We can be more precise than just judging by eye. By using the Pearson coefficient we can measure the level of correlation, with zero meaning no correlation and one meaning perfect positive synchronisation.

This reveals three things:

- There is a strong correlation between the average scores of critics and film audiences.

- It was never complete synchronisation, which is the same story told in the previous section, looking at genre differences.

- There has been a de-synchronisation taking place fairly consistently over the past two decades.

What is behind the de-synchronisation?

I dug a little deeper into the data to see if I could identify what’s caused this de-synchronisation. I found a couple of key factors that explains at least some of this shift.

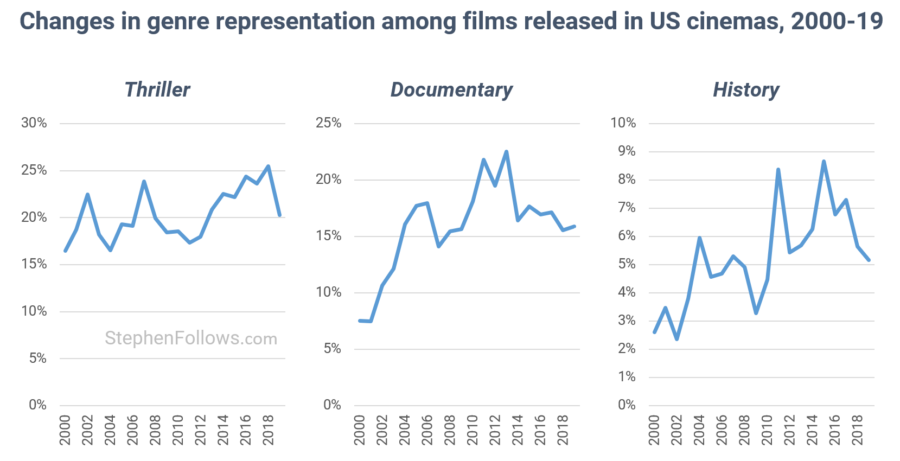

The first relates to what we’ve already seen, namely differing genre tastes. Three of the four most divisive genres have all seen a relative increase over the period (with the fourth, Action, neither increasing nor declining). This means that a larger percentage of the films in cinemas are within genres audiences and critics often disagree about.

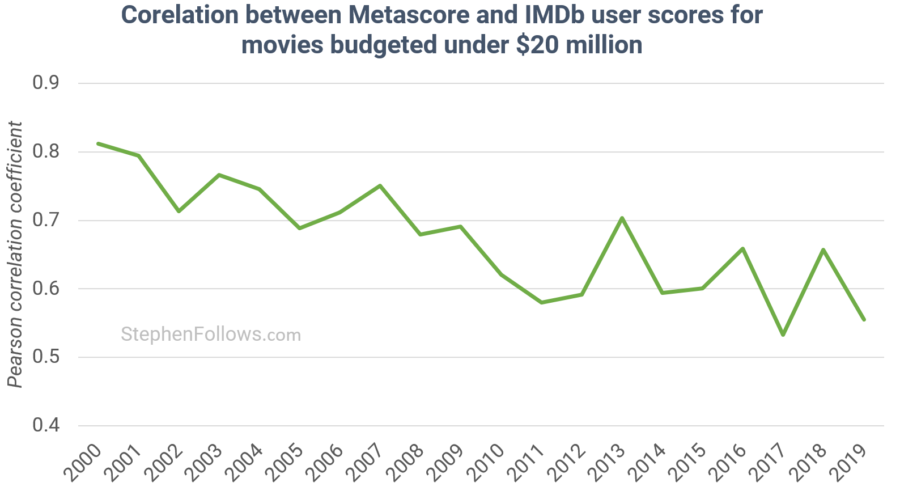

The second factor is budget. As making and releasing movies has become easier, we have seen an increase in the number of low budget films hitting the big screen. At the same time, these films have become increasingly more divisive, although I’m not sure why.

In short, critics and audience are disagreeing more about low budget films, all while a greater number of low budget films are opening in cinemas.

This gives us a (mostly) pleasing result. We know that the types of movies being released are changing and that they happen to relate to the types of films the two groups disagree about most.

The only unresolved piece of the puzzle is pondering why audiences and critics are moving further apart on the topic of low budget movies. Any suggestions would be welcomed in the comments below.

Notes

The data for today’s research came from Metacritic and IMDb. The criteria for inclusion into the dataset was all feature films released in North America between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2019, which had a Metascore, at least 10 professional film reviews, at least 300 user votes from male IMDb users and at least 300 votes from female IMDb users. I looked at the gender of the critics and audience votes but found no link to de-synchronization.

Comments

A more detailed study might look at the age, gender and race/ethnicity of the critics vs audiences.

https://news.usc.edu/144379/usc-study-finds-film-critics-like-filmmakers-are-largely-white-and-male/

Hi Jim. Thanks for your suggestions.

I did look at gender (audiences, critics and filmmakers) but didn’t find any clues there. You can read more about gender and film critics here https://stephenfollows.com/do-male-and-female-film-critics-judge-films-differently/

The age and ethnicity of the audience and critics have not changed dramatically enough to explain this recent trend.

Maybe the age, gender and ethnicity didn’t change much, but what about the views that the public and critics hold in relation to age, gender and ethnicity?

I know that personal experience is not an objective information, but if I may… in my experience these topics are becomming more and more common in various media and are becomming bigger and bigger focus for many different target groups.

Isn’t there possibility that differences between how audiences and critics view age, gender and ethnicity may cause divide how they rate the movies? Movies like the Star Wars sequels show that there is big divide in how individual groups view gender, race, and their “proper” representation in movies.

So how about checking cultural change?

My guess would be that higher-budget films tend to be produced in such a way as to please the largest number of people (so as to recoup their budget), whereas lower-end films are inherently a more niche product. French New Wave style experimental films, indie arthouse darlings, and ‘socially aware’ films produced on a shoestring may share the category of ‘low budget’ with the work of Andy Sedaris and Troma Studios, but that’s about it.

Speaking very broadly, people like ‘Big and Good’ films for largely the same reasons, but they *forgive* small, niche products for very different ones. Critics are going to be pretty harsh on ‘guilty pleasure’ films, especially those with retrograde or exploitative themes, while casual viewers aren’t as apt to award a high score for a picture that “I didn’t enjoy, but I admire its experimental effort to advance the medium of film as an art form” or sentiments to that effect.

Another issue may be homogeneity versus heterogeneity in the samples. Again, big movies tend to be broadly appealing, but niche films that do well with affluent, well-educated people from coastal regions are going to disproportionately please critics.

Finally, there’s the issue that critics review movies for a living, the casual audience reviews movies if and when they feel like it. The audience that *likes* some small, low-budget, guilty pleasure film may be small, but they’re also likely to be more vocal and thus likely to go give it a positive rating on imdb or Metacritic. So, you may be seeing bad films getting an artificial uplift in audience score there, simply because the audience reviews are self-selected. I’ve noticed a similar trend on Steam reviews for video games–the people who rate it are the people who bought it, which means the audience scores are almost always artificially inflated, simply by dint of “people who aren’t interested in this to begin with” having not bothered with it, and thus you’re polling a sample that’s already predisposed to like an “objectively inferior” product because it hits their particular tastes.

Hi Stephen, as always a thorough and compelling study.

Although it’s something that cannot be examined by data, I think, one area which should be factored in is the way a film critic approaches a film. He or she may have a certain delight in the esoteric approach to cinema that is not always shared by the public and which can, in some cases, lead to a certain amount of self-importance. And I should know. I reviewed films for the whole of the nineties for the BBC and local press in Manchester rarely missing any new releases. With this luxury and dream job though comes a responsibility and after a while it became obvious that I was suffering from Movie fatigue.

It was easy to dismiss much of Hollywood’s fare as formulaic and worthless because we had seen too much and seen better. Some of the movies I panned were perfectly good films and many were extremely successful and popular with audiences, but for me they were dull, and despite fabulous production values left me cold. Mark Kermode (Film Critic BBC) was one of my contemporaries and he said: “You have to see everything so that when something comes along that is good you will really notice it.” Of course, this exacerbated the fatigue and often meant that we were too quick to judge, and after a while, very little appealed because we had set ourselves far too high a standard to be realistic about the film’s quality.

If you look at the reviews in The Guardian, you will see more bad reviews that good. You might argue that a bad review is much better copy than a good review so there might be an editorial decision in there. To a certain extent Movie critics can be a poor parameter for quality and an injudicious contribution to its success or failure.

After ten years of reviewing films, I knew it was time to stop. I wasn’t enjoying it and I was probably doing some disservice to the film industry. Less is so much more. Harry Stafford – The Manchester Film School

I salute your honesty, Harry. I used to vote for 2 annual awards but had to let one go when the viewing started to feel like homework. The best approach to minimise general grumpiness, as well as unconscious bias IMHO is a decisive attempt to look at every work afresh.

Hey Harry, very interested to read your reply. I too am a film critic and have been one for 30 years now. But I have only managed to maintain my career in this field – where I saw movie fatigue heading my way early on hosting film shows on TV and Radio – by shifting the focus of my criticism and not accepting that i need to see everything. Not least because, when I started out 4 or 5 films were released per week max and that was still a commitment, now it can be double that. The fact is we have our areas of interest and expertise and I don’t believe I need to be able to reference every film ever. Not least, because as time goes by, the number of films ever released increases, making it increasingly ludicrous to think new critics can see everything. I believe it’s therefore imperative to make some discerning choices these days as a critic and perhaps become a specialist to some extent. Not least because criticism now requires an understanding to sociopolitical factors and discourse since MeToo, BLM etc. that cannot be ignored. In recent years I have reinvigorated my criticism by focussing on inequalities in the profession and how that impacts what we see onscreen – especially in the light of the aforementioned social movements. My academic research has now turned into a podcast – Open To Criticism. Perhaps you might enjoy it! All the best, Wendy. https://podfollow.com/open-to-criticism

Is there a link caused by the change in composition of reviewers? e.g. rotten tomatoes added 600 new reviewers (mostly from non text digital media) across 2018/2019 and this coincided with the low point in the correlation between critic reviews & box office results (though there’s a decent amount of variation in those numbers). Can you see if anything like that is impacting the skew?

Check out this ringer piece on RT & user review correlation to box office success (which is, when properly adjusted, a tangible expression of user interest).

https://www.theringer.com/movies/2020/9/4/21422568/rotten-tomatoes-effective-on-box-office

Is this result, I wonder, another expression of the contradiction inherent in our industry, requiring us to surprise our audience with a predictable experience?

Isn’t budget related to genre? The lowest budgeted genres (horror, documentary) also have some of the biggest divergence.

Hi Stephen

Would you please do a quick name and shame on the films at the far ends of the spectrum that are outliers? Like there are about 11 films that critics panned with less than 10% but score above 4.5 with audiences and about 5 dots that score below 4.5 with audiences but above 70% from critics? I’d love to know if the films in those clusters have anything in common?

Yes, I’m very interested to see which films had the biggest divergence, especially the ones that critics hated/audiences loved! If only so I can watch them and judge for myself lol

Is the $20 million budget inflation adjusted? Checking the inflation calculator, a $20 million budget in 2000 would be a $30 million budget in 2020, and a $20 million budget in 2020 would’ve only been a $13 million budget in 2000.

Could the fissure be, at least in part, a problem of the modern liberal mind which has been enculturated in a certain form of intra-social critique, and is in consequence much given to ideological contempt of the masses.

IMDB users are not “the broader public”: there is no way of finding this out but I would imagine the demographic is severely skewed, Not only that but reviews are not independent of critical ratings: a critically highly rated film is more likely to fail to live up to expectations.

Surely a better way to look at this would be to correlate critical score with box office returns, both total and relative to budget.

Critics that grind out reviews as Mr. Stafford describes should take breathers–they can have my oxygen if they’re desperate. Siskel & Ebert’s Thumbs-Up/Thumbs-Down approach determined whether audiences should watch a movie as genre fans (Star Wars got panned but made bank), or if a film displays different or unusual effects that transcend narrative faults (the first Suspiria’s elaborate cinematography & atmosphere). If a film fails to appeal on either level, even a gentle tickle, then 2 thumbs down. I respect this approach better than abstract numbers.

Critics stopped putting themselves in others’ shoes. Call it intellectual autism, where they lack Theory of Mind (i.e. a notion that people can think differently from the critic’s preferred society). It causes consternation around award ceremonies. “Who in the guild thought this movie deserves one when it neither entertained nor respected all audiences’ intelligence?”

Another measure of loyalty far divorced from brand or genre, “group-think loyalty”, compels incessant clapping in fear of stopping and getting labelled a categorical traitor. These critics wish to exude an aura of cool (i.e. do not abide the unwashed, vulgar crowd) and fit in. Hence, they praise movies that cater to their group’s sensibilities instead of their own and upon the backs of genres and audiences who got snubbed via undelivered promises.

This explains The Last Jedi. Just because you can “de-construct” or “subvert” does not mean you do it to a sacred cow without discernible finesse (which never appeared). Critics associated with so-called post-modernist thought had to clap just for the privilege to criticize movies for a living. Once critics stopped caring about cultures besides their own, outliers started debating whose taste in what socks had entered these impostors’ mouths.

As for low-budget films and the Rolfian democratization of entertainment via venues like YouTube, they put industry giants on their toes. Hence, everyone becomes and stays hungry, remembering to communicate with audiences instead of being merely clever. For a small guide on a long history of Side Orders and Missing Gems, click https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYNH__okGjU&list=PLU0Cu1gVmh2dCdxM2o8pcN7lcH6Xe-a9y&index=129 (Good BAD Flicks) and see how a movie pulls through despite an awful reputation. This guy’s Channel is awesome.

Another Channel named YellowFlash2 referred me here. He also nitpicked an article by Robbie Collin that passes the data off to problematic “Internet Warriors”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXaFnTxxoIc I cannot believe these people are that deluded, but they are. That’s so you know: never mingle with them, never discuss them as being legitimate critics.

Two words: Culture War

It could possibly be explained by the recent divergence between right and left. More information could be found by reading Jonathan Haidt’s work. There is definitely correlation. Films are largely rewarded at the Oscars for having particular themes. Critics are largely from the humanities which is a largely far left affair. 4 percent of academics in the social sciences are on the right here in Canada. The skew will be much higher in the humanities. One could test third, but sorting critic political views would be time consuming.

New follower, first time commenter 🙂

Thank you so much for these articles. As a filmmaker and film teacher, these are invaluable resources.

I wonder if you have given any thought to how “animation” is often misidentified as a genre rather than a medium? The medium has always suffered from this lack of designation. I would argue that most American animated films are rather “Family” in genre, instead, and having such disparate responces in the data would result in a different outcome if they were more properly combined.

When it comes to the lower-budget movies there are two types of those: the “crowd pleasers” using cheap thrills and controversial approach to compensate for lack of money and the “Festival Darlings” – movies that feed into idea of low-budget films giving the voices to the marginalized groups. The latter ones might be not pleasing to the audience, but that never matters – it’s what the movie stands for does. In other words, if you trash “Moonlight” – you, as a public figure, will be seen as a bigot, while the original “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” was never designed to appeal the traditional critics (and many contemporaries hated that movie when it first came out). So there’s more incentive for “TCM” to please the audiences, while “Moonlight” was clearly produced with the thought “Don’t bother – this movie is untouchable: it checks all the marks”, so more effort was put into making “Moonlight” immune to criticism, than to make it appealing for the broader audience.

Never forget about Harvey Weinstein, who – whenever he wasn’t busy on the “casting couch” – put a lot of effort to askew the image of the “auteur” movies, making the studio projects look wild enough, while being safe enough and butchering the actual indies to fit the current critics’ tastes (like “54” – that he deemed “too gay” for the 1990s). He kinda pioneered that approach that the Hollywood studios still use. Big Hollywood studios.

Like “Universal” (a.k.a. “Focus Features”), or “Paramount” (a.k.a. “Lantern Entertainment”), or “Sony” (a.k.a. “Sony Classics”… dude – they’re not even trying). Many low-budget movies are catered to those studio brands designed not to make money, but to serve as the gatekeepers of the auteur cinema, while eliminating competition.

Therefore – there are two kinds of low-budget films: the ones with blood, boobs and beasts – and the ones with socially important messages that feed the illusion of the Hollywood corporate inclusivity.

Fun fact: when Kubrick’s “The Shining” first came-out – the critics panned it… but as soon as the movie became a commercial hit – they turned around.

Critics have been out of touch for a while. An easy example of one a startling difference is clear on rotten tomato ratings. Frequently, you see the audience rating and the critics are very different.

I wonder if something else hasn’t entered the equation separating critics and audiences — something like (for the lack of a better term) “loudness.”

Studio films with wide releases have a great reach and dominate a culture that is inherently loud. By contrast, smaller independent films have much less of a reach and are therefore less ‘loud.’ What if audiences are now unconsciously incorporating that loudness into their calculus for how they respond to a film — and, quality or not, smaller films are dinged for their inability to be heard in a loud world.

Audiences (who might be anxious at their own inability to be heard) are therefore constellating around the loudest films and, for them, quality is a diminished standard by which movies are judged.

Thoughts?

Hi James

Good thought. It’s certainly the case that critics and audiences engage with films in very different contexts. Critics see them first, before most of the hype and coverage and do so in quiet, rarefied environments. They are also more likely to be battle-hardy over marketing messages around movies. On the flip side, audiences will see a movie after they have seen buzz, social commentary, marketing, promotions, etc and with a load of other people.

But the key question is – has this shifted recently? Marketing is evolving but I don’t know if movies are any less “loud” than they were in the 1990s.

Thanks for replying, Stephen!

I guess I’m not saying that movies are less loud — in that regard, I’m not sure that in the aggregate that they’ve changed at all. I’m saying that the audience is changing and is increasingly constellating around the louder, bigger voices — irregardless of quality, likability, etc.

As a thought experiment I think of the entire audience as being in a school gym: in one corner is a big studio film that everybody’s talking about, and in another corner is an independent film with no names that is widely recognized as the best movie of the year.

We’re asked to pick sides — and while the big studio film might’ve done well in the past, these days it’s winning a GREATER share of the audience principally because of its size, reach and loudness — the studio is winning and the audience increasingly wants to be part of a winning team.

I think this is what’s changed — it’s an additional standard that’s been added to our list of reasons why we do or do not choose the movies we do.

Anyway, thems my thoughts. Thanks again for replying!

I would prefer a plot with the budget on the x axis and the correlation coefficient between both scores on the y axis. This would more clearly show whether audience and critics disagree more on low budget films. If so, we would expect the curve to go up with from left to right. Of course, one would have to group the budget on the x axis in order to get enough films per group, e.g. in 10 million steps.

Great study!

(Sorry I’m not english speaker.)

A possible reason for de-synchronisation I didn’t see everyone mentions is: Critics have less influence. Not long ago I watch a famous chef on Youtube said: years ago if you get a good review from critics, you can expect 6 months good revenue, now critics are nothing, people only care what their friends say on internet.

My point is: Social media make critics less influence on audiences, therefore creat de-synchronisation.

You’re right about that. And that would hit Disney’s Star Wars Sequel Trilogy hard.

Preface: I am a “bi-racial” person.

Opinion: It’s the reason why I personally have checked out of most modern movie watching. I believe the invisible thread is called ESG rating (Environmental Social Governance). US corporations are financially incentivized to meet certain quotas w/ hiring “under represented people” (females, people of color and especially black people) to get an ESG rating that in turns attracts investors and mitigates risk for stock holders against activism and “cancelling of assets.”

Many critics either write for corporations or aspire to and therefor are at risk of public backlash for criticizing a “minority” lead film. If anybody in the industry casts a member of these groups in a negative light, they may be accused of contributing to social injustice. Even if a movie goes so far as to endorse a form of “reversed” discrimination by a minority film, the danger remains.

This seems to create an environment of heightened fear for critics as their livelihood could be affected.

Ex: Jurassic Dominion was written by a woman (who had only written a short film) and contained intentional feminist messaging that they signaled during a Vogue article on the film. You may disagree w/ this ideological approach to filmmaking but it helps the studio’s ESG score.

Much to the chagrin of studios execs, ordinary fans and movie goers are creating an increasing counter movement online, championing story-based filmmaking over ESG-based filmmaking.

If we look at critics we see a reflection of a sectarian social political ideology perpetuated by ESG. If we look at movie goers, we get feedback from individuals who’s lives are not influenced by an ESG score, and therefor speak their personal truths. Although I appreciate diversity and equality, I think ESG is having an insidious affect on the purity of creativity and entertainment with my most beloved medium: film.

And creating a divide between critics and movie goers (the customers). Thanks for the article!

Film and media in general has become more about delivering a highly politicized message that falls in line with 21st century socio-political narratives more so than delivering a story. The most important things to show in film in our generation are diversity, feminism, LGBQT representation, gender fluidity, etc. rather than delivering an engaging plot, talented actors, and immersion.

What do these political narratives have to do with Tolkien? Or vampires? Or space operas? When did the story and the fictional world become subservient to our post-modern identity politics? If I wanted that I’d head down to a drag show, BLM protest, or a gay pride parade. I don’t need it in worlds that are supposed to be wholly different than ours. Their differences is what makes them entertaining to watch.

Critics are more concerned about checking off boxes that satisfy the Bechdel test and diversity quotas. They have no interest in what actually makes films good.

Audiences do.

All this talk in the comments section of political differences is absolutely wrong. No, it’s not that. There are simply not enough people to whom the sight of a brown (or gay) person in a film causes them to hide under the floorboards. Films include these elements because they meet audiences where they are in modern culture. There are not enough stunted throwbacks to the 50s to effect any of this stuff.

What’s really happening is that the divergence is caused by differing context. Critics try to view films as if they are completely devoid of context, but modern films incorporate this context (trailers, popcultural history, articles, even Twitter commentary) into their narrative, as well as often being part of a wider tapestry of an extended universe, reboot, sequel etc. This is why there is a divergence between audiences and critics.

Not because of some narrative proposed by loud alt righters on YouTube trying to weaponise popculture to radicalise gullible rubes into fascism.

Great subject/question. I am genuinely fascinated by the general “hype buzz” some films seem to get, that to me seem at best average. The critics are certainly part of this. The “Knives out” series is probably the best example recently, although to be fair I think it might have something to do with a cultural appeal to the USA audience that I am missing. When it was mentioned on a major Uk centric social media post I spent a good 20 minutes reading comments which were around 90 percent critical of the film. Yet the general press rave about it as a success? Nobody here seems to have suggested there is a relationship between the money and system, can a Netflix juggernaut really be critiqued openly by paid professionals?

Hi Stephen,

Interesting analysis.

A couple of graphs that I think are left off here: namely the absolute difference between critic and user scores over time–has that grown larger? Also, has the variance increased over time?

If you have the data set somewhere, and maybe if it can be updated through 2023, I’d love to take a stab at it for fun. Thanks so much.