ABBA’s music is immortal, Swedishly engineered to flood listeners’ brains with dopamine until the sun explodes. The band itself, though, was never built to last. Its lineup included two married couples — Agnetha Fältskog and Björn Ulvaeus, and Benny Andersson and Anni-Frid Lyngstad — whose relationships ended in double divorce, triggering the group’s 1982 split. ABBA’s original career spanned just a decade; they stayed broken up for the next four, even while the Mamma Mia! movies and a relentlessly popular greatest-hits album made them more famous in this century than they’d been in the previous one.

They were once offered $1 billion to reunite, but seemingly nothing could compel them back into business with their former spouses. “Money is not a factor,” Ulvaeus once said. “We will never appear onstage again.”

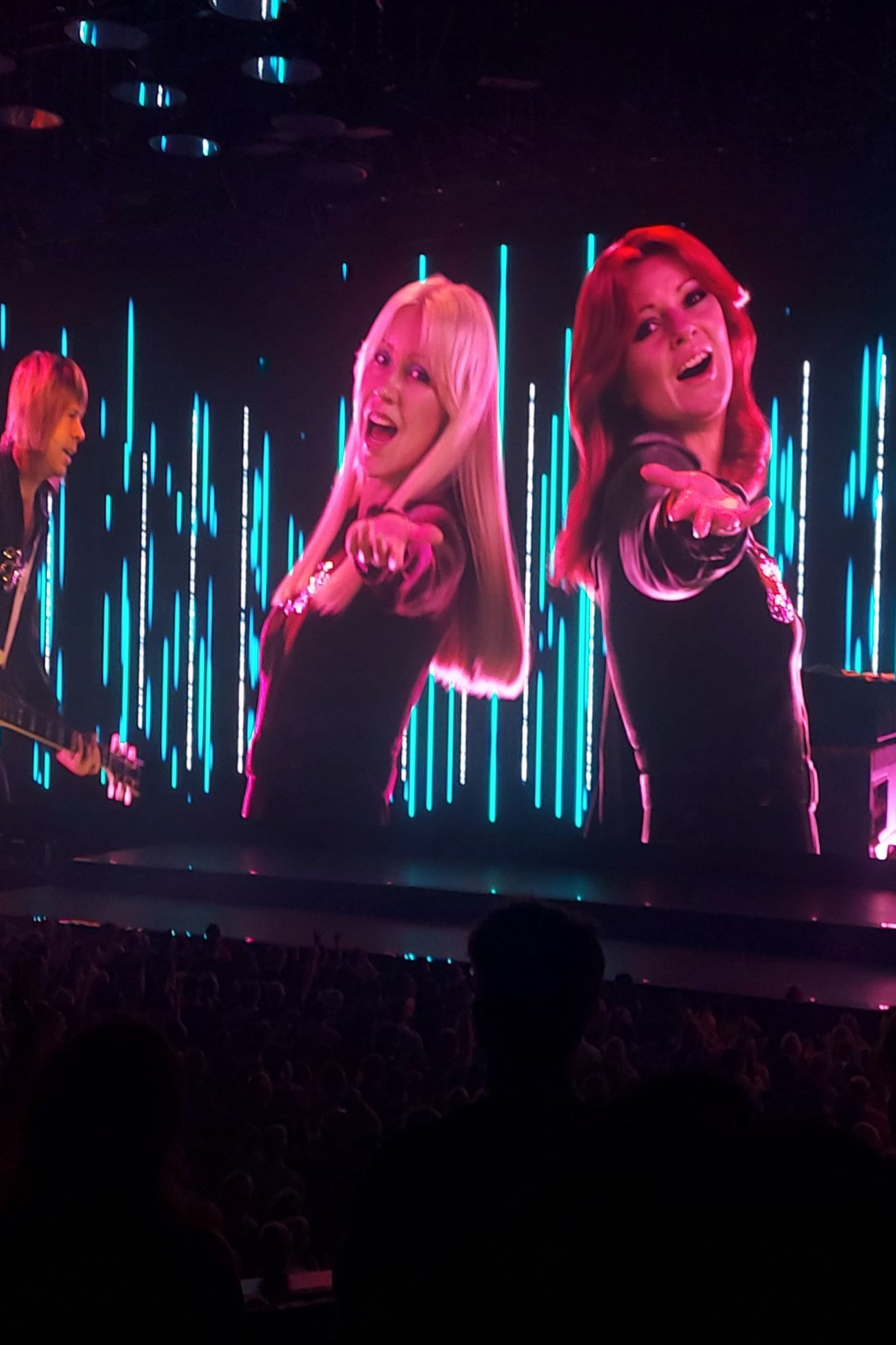

But then, this past May, they did. The occasion was the opening night of ABBA Voyage, their new virtual-concert residency in London, and they were there to take a bow for a performance they had not (technically) given. Voyage stars computer-generated clones of the band designed to look and sound like their 1979 selves. The real members, now in their 70s, spent a month in motion-capture suits working out the choreography but can now relax at home — separately — while their “ABBAtars” play “Dancing Queen,” “Fernando,” and “Waterloo” seven times a week, aided by a ten-piece live orchestra.

Voyage takes place in a custom-built temporary stadium, ABBA Arena, and cost $175 million to develop, making it one of the most expensive live shows ever. It’ll need to attract north of 2 million fans just to break even, but that seems doable with 650,000 tickets already sold. Performances will likely continue through at least 2025. Once start-up costs have been recouped, profit margins could dwarf that of a typical reunion tour. And things could get even more lucrative from there with plans underway to launch a second version of the show in a yet-to-be-determined city.

Since 2012, when a somewhat glitchy Tupac played Coachella, virtual-concert technology has mostly been used to resurrect dead musicians. Fans have responded poorly to digital revenants of Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse, and Ronnie James Dio, who never could’ve imagined they’d be reincarnated as CGI, much less given their approval. Each was decommissioned under a cloud of exploitation. (Fully synthetic performers like the Japanese software diva Hatsune Miku have fared a little better.) But ABBA’s members — who are alive, consenting, and profiting from their show — may have finally destigmatized the concept. Their success suggests that the single best use of the technology may be for living artists who hate performing, or their bandmates, or both.

The seeds of the idea for Voyage were planted by Simon Fuller, the former manager of the Spice Girls and creator of many international variants of American Idol. In 2016, he partnered with Pulse Evolution, the company whose founders had digitized Tupac and Michael Jackson, and set to work on an Elvis Presley hologram that never made it to the stage. “Fans are cynical about reinventions of their idols,” Fuller says. “I realized that if I wanted to bring someone back in a way that was acceptable, they had to be alive. That way, the artist would be around to talk about it and fans would be less likely to argue with their hero. And ABBA — forget Pink Floyd, forget Led Zeppelin — was the holy grail of my vision.” He pitched the band. “Initially, they were like, ‘What is this?’ ” he recalls. “But it was a bloody good idea and they understood it.” (Fuller ended up not being involved in the final version of Voyage.)

ABBA also understood that Voyage would scramble the usual compact between artist and live audience. Since Fältskog, Ulvaeus, Andersson, and Lyngstad are theoretically capable of performing but simply don’t feel like it, they needed to entice fans with something their physical presences couldn’t offer. So they digitally de-aged themselves to their ’70s heyday, which may allow attendees to feel de-aged too. “That wasn’t just to be young and good-looking. It was to validate this exercise,” says Fuller. “If it was just, ‘Oh, we’re mo-capping ourselves now,’ then a fan might say, ‘You don’t want to play to us?’ But these immortalized avatars are a fun fantasy.”

That fantasy required some heavy new tech. Even though musical holograms have been around for more than a decade, most of them still seem like they came out of the tinny rendering engine of a Nintendo 64. So ABBA hired Industrial Light & Magic to re-create their classic-period look down to every strand of hair and facial tic. The ABBAtars are the most lifelike virtual pop stars ever rendered, and it’s not a close contest.

There was also the issue of display. “We saw some hologram shows and thought, This is not good,” says Per Sundin, the CEO of Pophouse Entertainment, a co-developer and lead investor in Voyage. Most so-called holograms (including the ABBAtars) aren’t really holograms. Many are just variations on a 160-year-old illusion called Pepper’s Ghost, in which a three-dimensional figure is projected onto a transparent screen. “You have to stand right in front of it to see it, and after ten minutes it’s boring,” says Sundin. “We wanted something that would feel immersive for 90 minutes.” Thus Voyage uses three enormous 65 million-pixel LED TVs to maximize clarity and viewing angles. The ABBAtars appear in human size on the main screen and in magnified close-up on both side panels, mimicking the effect of a normal concert.

In some ways, Voyage may be better than an in-person reunion. Since no traditional venues could accommodate the show’s hardware, the band had to build their own in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Its maximum capacity is just 3,000, which is more intimate than anywhere the real group could ever play. “ABBA could do a tour of small theaters,” says Fuller, “but there would be millions of fans who couldn’t get tickets, and you’d be charging so much money that everyone would hate you.” (Tickets for Voyage range from around $25 to $200 for a spot in a ten-person VIP booth with a private dance floor.)

Not every artist will be able to splash out $175 million on bleeding-edge CGI and a custom stadium. But now that ABBA have done it, others may not need to. Sundin says the band and its partners could lease their tech and arenas to other superstars. There’s also the MSG Sphere, James Dolan’s futuristic 17,500-seat concert venue with even bigger LEDs than ABBA’s, set to open in Las Vegas next year (with an identical twin proposed in London). And for smaller artists, there’s a fast-growing industry of start-ups offering hologram tech that can be permanently installed in venues or sent out on the road. (One such venture is Proto, an L.A.-based company that builds phone-booth-shaped displays that musicians like Kane Brown and Walker Hayes have used to beam into concerts remotely.)

ABBA “worked out a lot of the issues, and now we’ve all got more options,” says Fuller. “Artists who want to do things the way they’ve been done since time began can continue to do so. But if others want to stray into the virtual world, Voyage is proof of concept.”

That proof of concept may have arrived just in time, as many top-grossing touring acts approach the end of their performing years. Mick Jagger has called Voyage a “technology breakthrough,” and at 79 years old, the recent heart-surgery patient is presumably aware that the Rolling Stones can’t rock in corporeal form forever. Same for Carlos Santana (75), who collapsed during a gig this summer; Paul McCartney (80), whose voice is finally waning; and Bruce Springsteen (72), who’s starting to look like Woody Allen.

They may already be planning to replace themselves with virtual doubles. “I can’t say who, but we’ve been filming artists now while they’re well enough,” says David Nussbaum, the CEO of Proto. “So when they want or have to stop playing live, they’ll have holograms that have been endorsed by them and not just their estates.”

Since Jagger and McCartney have quenched fans’ demand with regular

in-person touring, though, “the real opportunity is fractured bands,” says Olivier Chastan, the CEO of rights-management company Iconoclast, which owns the music catalogue and likeness of Robbie Robertson. (His band, the Band, hasn’t played together since The Last Waltz in 1976.) “Do you want to see Fleetwood Mac with Lindsey Buckingham? Or the Beach Boys with Brian Wilson and Mike Love? Of course. In most bands, you eventually have dissension and then nobody will talk to each other. But this can solve that problem.” For example, Oasis have been hopelessly split up since 2009, but Noel Gallagher says he’d consider performing with a Liam hologram.

The losers in all this may be young artists, whose music already accounts for a diminishing share of total listening. (In 2021 and the first half of 2022, consumption of current music declined while that of catalogue music jumped by double-digit percentages.) What happens when they have to compete against not just a bunch of old songs on Spotify but touring versions of the greatest acts of all time, virtually reassembled and restored to their peak concert-giving powers? Chastan hopes those younger artists will use the tech in more creative ways than their elders. “A band like the 1975 could do an augmented-reality show with Stranger Things–style special effects,” he says. “Or someone could just use it to sell merch: ‘Click here to buy what Harry Styles is wearing onstage right now.’ So it could be amazing. Or it could be irritating.”