Why Adele is Bond and BTS is Squid Game

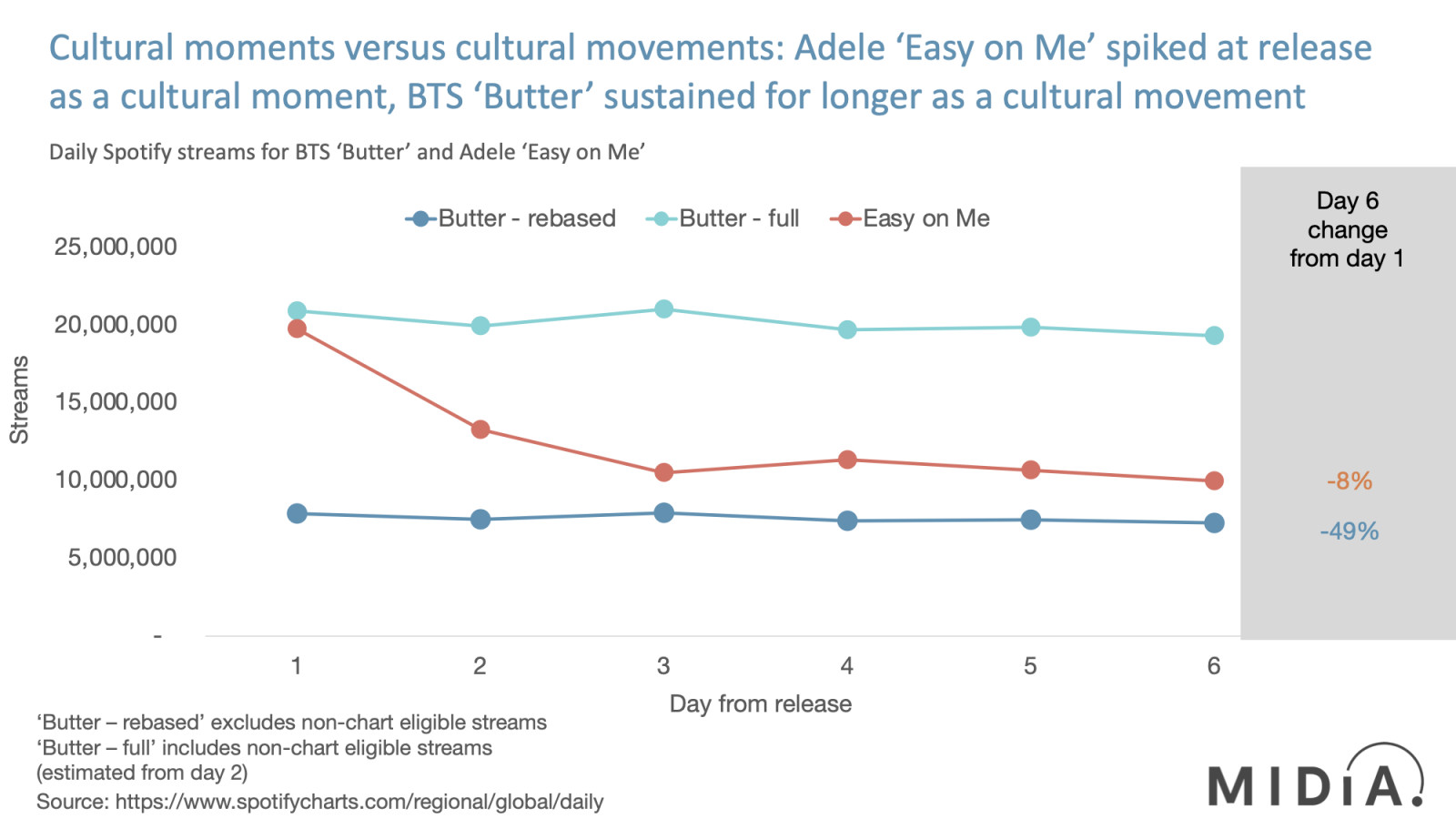

When Spotify announced that Adele had broken the record for the most streams in one day, with 19.8 million streams, the caveat was that this was true as long as you do not include all of the streams BTS had accumulated in 24 hours for ‘Butter’ in May. ‘Butter’ racked up 20.9 million streams, but 10 million were wiped from the record for ineligibility, thus only counting the first 10 plays per user in any given 24-hour period. While the caveat makes sense from the perspective of countering chart manipulation, it also raises fundamental questions about just how we measure success and whether, what are fundamentally subjective definitions, discriminate, intentionally or otherwise, against certain types of fans and music.

Fandom is fragmenting

We are living in the age of fragmented fandom where niche can feel mainstream, and mainstream can feel niche. Central to this is the shift from cultural moments to cultural movements. In the old, mass media world, most people experienced the same TV shows, movies and songs, with mainstream media promoting a relatively narrow selection of titles to the majority of the population. Now, audiences are fragmented and marketing is more targeted. So, it is possible for something to feel entirely mainstream to the target audience, even though it may not even register for the majority of the population. Whereas big, old-school releases resulted in water cooler, cultural moments, successful niches become cultural movements, driving sustained engagement and cultural capital among their respective audiences.

Bond vs Squid Game

Nowhere is this seen better than in the successes of Squid Game and James Bond’s No Time to Die*. Bond was the cultural moment, with wall-to-wall mainstream media support and is close to crossing $500 million in box office receipts. Squid Game is Netflix’s most successful show to date with 132 million viewers, but was only watched by a minority of the total population in most countries. Nonetheless, it has become a cultural movement, seeping across popular culture via memes, social posts, fan content and so forth. Bond’s box office receipts translate into about 25-35 million viewers, while Squid Game is estimated to be worth around $900 million to Netflix. Bond was the global cultural moment, but was actually smaller on all counts than the less ‘traditional’ mainstream Squid Game.

Featured Report

Visionary audio Unlocking the power of video in podcasting

YouTube may be the only viable platform for long-form video podcasts, but that does not mean audio-first podcast platforms should abandon video. Instead, podcast platforms should leverage video both as...

Find out more…A similar dynamic is at play when comparing BTS’ Butter with Adele’s Easy on Me. Easy on Me was the cultural moment, with the massive initial wave of listening soon dropping off, while Butter was a cultural movement, which sustained throughout the first six days of release at pretty much the same level. Adele was Bond, while BTS was Squid Game – perhaps no coincidence that their nationalities match, too.

Adele was still the bigger success, but only if measured by the way the music industry wants it to be measured, i.e., discounting all those extra BTS Army plays. But what if a 13-year-old BTS fan simply wants to listen to the track 20 times in a day because they love it so much, while an older Adele fan listens to her tune a couple of times in the evening after work? The way we measure success inherently suggests the former behaviour is invalid, while the latter is more valid. The system favours casual listening over super-engaged listening. Listen, I am fully aware that the BTS Army is renowned for caning BTS tracks 24-hours a day in their thousands. But the risk is that the baby is getting thrown out with the bathwater.

Converting success metrics

So, why does this all matter to music? Quite simply because, just as in the TV and film industry, traditional metrics are still used to measure success – even if the old units of measurement have progressively less relevance. Music charts especially so. Since the advent of music downloads, the music industry has continually revised its definitions for ‘sales’ in order to try to make the old ‘cultural event’ measures work for a world that is increasingly shaped by cultural movements. The industry and media both like being able to talk about ‘sales’ and platinum releases – it is convenient short hand. But, if a platinum certification from 2021 is not equivalent to one from 1991 then does it really serve any purpose?

All of this would be a minor inconvenience if it were simply a ‘currency exchange’ issue, e.g., understanding what a million sales in 2021 was versus 2020. But it is not just that. The current measurement frameworks are biased towards artists that fit better in the traditional artist model than the new, emerging one. Including all BTS Army plays is probably as wrong an answer as discounting half of them. But a solution does need to be found, one that better captures the impact of a song on its fans. Perhaps a blend of measures that incorporate number of listeners, number of listens per listener, and total number of listens. (Also, there is a strong case for treating lean-back plays differently than lean-in plays – both in terms of charts and royalties). Each measure would be useful in its own right, which implies there may not be a single measure anymore. But, given the fragmentation of fandom and the growing diversity of fan behaviour, that is probably not a bad thing. The days of trying to measure every artist and every release by the same metrics will eventually become a thing of the past, however inconvenient that may be.

*Why did James Bond go grey? No time to dye…

There are comments on this post join the discussion.